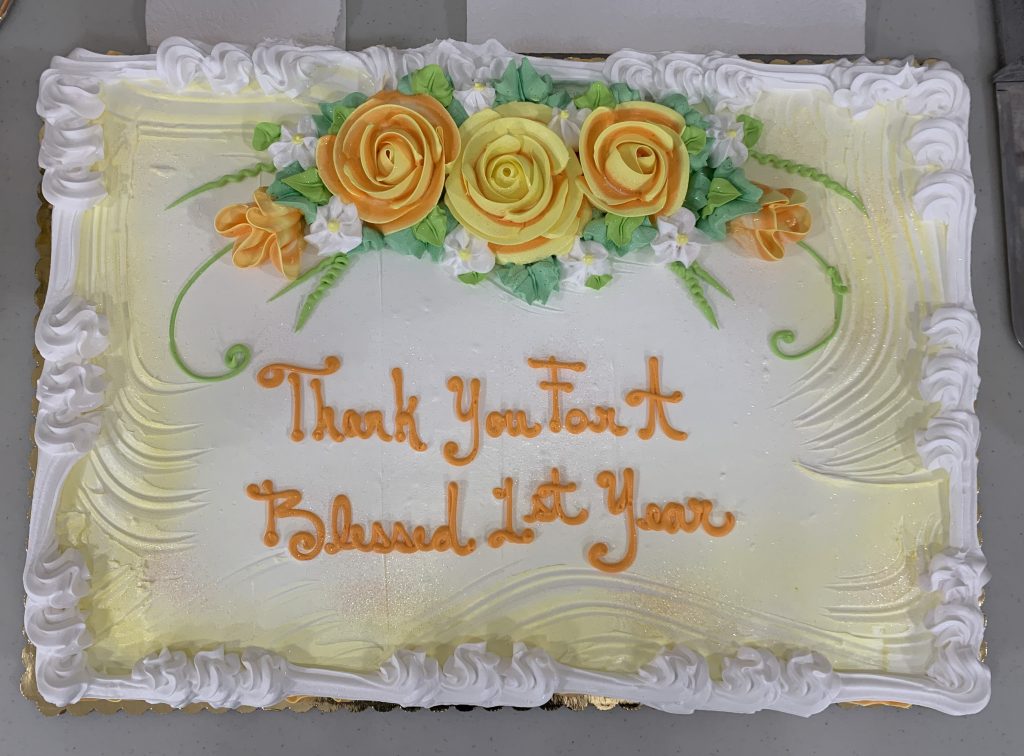

Celebrating One Year of Service

On January 15, 2023 we celebrated Pastor Nat Erickson’s one-year anniversary with First Baptist Church. The Erickson family moved into the church parsonage on January 20, 2022, and Pastor Nat preached his first service on Sunday, January 23. The church has been blessed by his leadership and guidance, and whole Erickson family’s presence and involvement in the life of the church. Thank you, Ericksons, for the blessings you have brought to us!

Erickson Family

Flower Bouquet

Cake

January 29, 2023 Church Service

The rest of the pattern: keeping Sabbath

Sabbath. God says, “Remember the Sabbath by keeping it holy” (Ex 20.8, NIV), so it must be important. What is the Sabbath? When is it? Should we keep it? Maybe you have a moment to think about those questions. More than likely, though, you’re just too busy to even know or care. In a world of restless and relentless busyness—with more piling up as you read—what should we do about the Sabbath?

The word “Sabbath” is just an English version of a Hebrew word. It means “rest,” or “cessation.”

The Sabbath in the Bible

Before considering some of our own time and culture, let’s take a moment to consider a little of what the Bible tells us about Sabbath. In the Old Testament, Sabbath is incredibly important.

- Sabbath is a weekly reminder that God completes his work, teaching the people to hope that God will do it again.

- Sabbath is a holy time in the best interest of the people and the animals in God’s Kingdom.

- Sabbath is a sign that God set Israel apart for a special relationship with him.

- Sabbath is a reminder that Israel was slaves in Egypt but have been redeemed from servitude into life that involves rest.

- Sabbath is a day to celebrate that there is rest and cessation within creation, not just endless stream of more; that while there is much still to be shaped and done, there is much that is done and requires no more work.[1]

For reasons that I don’t want to delve into here (too long of a discussion), I don’t believe that we as followers of Jesus today are mandated to keep the Sabbath in the sense it’s talked about in the Old Testament Law. However, that doesn’t free us from considering the centrality of the Sabbath within God’s revelation of himself in this world. The Sabbath was not an afterthought or an accident. Sabbath is part of the foundational pattern of creation and of the way that time is meant to be marked, measured, and experienced. Within the order of creation, within the order of the way that God marks time, rest has a central role.

The Sabbath and Us

While we may not be mandated to keep the Sabbath as an expression of keeping God’s Law, we’re also not free to ignore the Sabbath as part of the pattern of creation. It may be fine for us to mark a different day than Saturday as holy (the Old Testament Sabbath), or to set aside different times within the week rather than a whole day, but for us to reject God’s pattern of setting aside time from the normal rhythm of work is to suggest that God’s plans and intentions are wrong.

Instead of equating Sabbath to Sunday (which is not bad, but not entirely necessary, either), let’s think of Sabbath instead as a pattern of working God-honoring rest into our lives. In a lifestyle of constant busyness and achievement, this pattern is not just about getting us some time to breathe, but teaching us to realign our hearts towards God and towards others in the right way.

You see, our hearts are desperately prone to idolatry, to fooling ourselves, and to avoiding the work of maturing in Christlikeness. Sabbath fights against all three of these issues. Sabbath puts us at rest before God and with others. Sabbath guards us against many key idols of the current era.

What idols? Consider with me 1) demi-god syndrome, 2) busyness as a distraction, and 3) busyness as self-worth.

demi-god syndrome

Demi-god syndrome is the belief or lifestyle which states that God needs me to be busy all the time because he can’t quite handle it without me getting things done. Whether driven by anxieties and fears, or by an overinflated sense of self-worth, or by having many abilities and needing to make sure things work great in different areas, demi-god syndrome is second nature to so many in our time and place. Well not said in so many words, those living with demi-god syndrome are laboring under the conclusion that God can’t hold things together without their constant input.

busyness as distraction from significant problems

Another destructive way that busyness functions in our lives is as a distraction from significant issues. There is a time and place for being busy in helping us through challenging times. But when busyness becomes a habitual way to escape the gospel and heart work needed to grow us in Christ-like maturity, we’ve got a major problem. When we start looking to busyness to give us what our hearts crave instead of turning to God who gives us rest and teaches us the path to wisdom, we are rejecting God’s work in our lives. For many of us, through habituation or difficulties in life, busyness has transformed into the normal way in which we get what our hearts crave—release from various burdens in life. God calls us to a much more challenging task than being busy. He calls us to the task of surrender and grace.

busyness as self-worth

Busyness also is a convenient way to judge your self-worth: “I’m busy, so I must be valuable.”

- I must be important because I have so many people with so many claims on our time.

- I must be important because I have visited so many neat places and done so many neat things.

- I must be important because I never have a moment to rest when there isn’t something else to think about.

And the logic of this delusion is so simple: people who are important have lots of demands on their time and have lots of people looking to them and often are busy doing many neat things in neat places. When our sense of self and value becomes tied up in being busy and in the many things that we do while we’re busy, though, we’re flirting with idolatry.

Sabbath as a trainer

In all honesty, our hearts are really deceitful. The old Greek dictum, “know thyself,” is easy to say but hard to do. Busyness is an easy pattern of life to fall into, because most everyone else around us is also busy. Whether you have already turned busyness into an idol like those above or not, the busy lifestyle we tend towards trains our hearts toward these types of idolatry. How do we counteract this idolatry-in-training? Sabbath comes to mind.

Sabbath is rest. It is meant to be a time of realigning our hearts toward God and toward others. In putting it in these terms, I want us to see that Sabbath is not meant as a personal spa day in which we get to take it easy and cater to our every whim. Sabbath is a gift and practice given to us from God to challenge the idolatrous tendencies of our hearts. It a time—whether a day or split up around the week—of worship and wonder, of celebration and joy. It should be a day to learn what is important, not just what is urgent and significant. Sabbath should rekindle our hearts with love towards God and love towards others.

How to Sabbath?

It probably won’t look like sitting in an uncomfortable chair all day long, trying not to talk to anybody or avoiding doing any sort of work at all. Here is one general principle:

If you work with your mind, Sabbath with your body; if you work with your body, Sabbath with your mind.

Do something which connects your heart back to God and others in a joyful way. This should involve Scripture, truth, and worship; this will probably involve some sort of Christian fellowship; and it can involve more than that as well.

But one thing Sabbath should not involve: being busy about things that you are normally busy doing. After all, Sabbath means cessation. It is hard to turn to the new possibilities of life with God in this world if you never stop trudging along, head down, endlessly focused on the next task in front of you. God invites us to take a break and find our bearings again. That is Sabbath.

[1] Summarized from Bruce K. Waltke and Cathi J. Fredericks, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2001), 71–73.

Post Photo by Jessica Delp on Unsplash

January 22, 2023 Church Service

The Strength of Tradition

Tradition is strong.

Tradition is strong like a straight-jacket, rigidly holding everything in place and constraining flexibility and innovation.

Tradition is strong like a brace, supporting a joint so that it can perform beyond its enfeebled ability.

That it isn’t, can’t be, strong in just one of these ways is what makes tradition such an insightful and challenging companion on the journey. Tradition is an endlessly inventive sparring partner.

The answer to who we are emerges in the discussion of the present and the past. Tradition is the major voice from the past.

The historic Baptist tradition

At the beginning of our series “Core Beliefs: Where Are We?”, we talked about our core beliefs and what they do for us. You can check that out here. In the preamble, we say that as a church we stand in the historic Baptist tradition.

There are good, bad, and ugly things about the historic Baptist tradition, itself a subset of the historic tradition of Christian orthodoxy (that is, right following of Jesus). The Preamble of our Core Beliefs summarizes a few aspects of this historic Baptist tradition. But here, I want to meditate for a little while on the value of standing in a tradition: tradition speaks into the present to help us better understand where we are in the midst of the fog. We will see that the historic Baptist tradition speaks with a helpful voice into current political questions.

Note that this post is longer than usual (~ 2,500 words, or about 2-3x longer than usual). Reader, you are warned.

Origin of the tradition

The historic Baptist tradition holds two important political values: liberty of conscience and separation of church and state. These two values are two sides of the same coin, answering the question, “What role should governing authorities have in the religious life of people being governed?” In the modern American context, we are used to the idea of separation of church and state.

What we may not have thought so much about, though, is that these values grew up in a very different time and place. When Baptists were first coalescing as a recognizable sub-group within Christianity in the early 1600s, basically everybody believed that the government should enforce “proper” worship in a state church. The point of separation of church and state within the Baptist tradition was that the state should not only tolerate different churches (or denominations) but that it also must not privilege a certain church. This is a long and interesting story involving many colorful people that can be read elsewhere.

These values which Baptists, among others, championed eventually—and often slowly and unevenly—made their way into the mainstream and are now enshrined in the US political system. The current multi-cultural, multi-religion US is the fruit of that legacy. People in the US generally believe that the system of government exists to regulate the well-being of how people relate to one another, but not to enforce or oversee the good of their souls by attempting to enforce religious observance.

Is our system the perfect solution to the problem of living together within a diverse society? No. But, looking back through history, I think it’s probably right up there at the top of ways that complex societies have yet come up with to enable diverse people to flourish together.

While the historic Baptist values of separation of church and state and soul liberty have largely gone mainstream in US culture, within the Baptist tradition they derive from certain theological convictions. Most importantly, the biblical convictions that 1) each person stands in direct relationship to God as an individual and 2) that true faith in Jesus cannot be legislated or coerced. Because of this understanding, we believe in tolerating members of other faiths so that their hearts can be turned to God through evangelism.

A contemporary conflict

Why belabor these points? Because in our current moment, the historic Baptist tradition speaks with a voice many Christians (and people who identify as “Christian” for political reasons) need to hear. In the current political moment, many conservative people—especially white Evangelicals, broadly construed—are talking about “Christian Nationalism.”

Paul D. Miller, an Evangelical sociologist, writing for Christianity Today, describes the movement this way:

Christian nationalism is the belief that the American nation is defined by Christianity, and that the government should take active steps to keep it that way. Popularly, Christian nationalists assert that America is and must remain a “Christian nation”—not merely as an observation about American history, but as a prescriptive program for what America must continue to be in the future. Scholars like Samuel Huntington have made a similar argument: that America is defined by its “Anglo-Protestant” past and that we will lose our identity and our freedom if we do not preserve our cultural inheritance.

Christian nationalists do not reject the First Amendment and do not advocate for theocracy, but they do believe that Christianity should enjoy a privileged position in the public square

Paul D. Miller, “What is Christian Nationalism?“

Whatever the particular merits of Christian Nationalism are—and for full disclosure there are people whom I deeply respect who describe themselves and their ideals as Christian Nationalist—we are wise to listen to the voice of the historic Baptist tradition we stand in as a church. The Christian Nationalist movement seems poised to try to push aside the values of liberty of conscience and separation of church and state. Giving special political privilege to Christianity and seeking to legislate Christian values on people who don’t want them looks like a rejection of the historic Baptist insight that the government’s job is not to enforce religious observance on people.

There is an important discussion to have about the degree to which Christian values represent values which are good for human society to follow in general. Some who fly under the Christian Nationalist banner appear to argue nothing further than this point. I agree in principle. When the Baptist tradition was solidifying, most people in “Christendom” broadly agreed to a general moral code that approximates many aspects of biblical virtues. That is clearly not the case today. But I would hasten to add that it is possible to labor for generically good social values and conditions without pursuing Christian Nationalism in the sense described above.

Appeal of Christian Nationalism

Christian Nationalism has some obvious appeal. In a cultural moment where Christian and conservative values—which are sometimes, but certainly not always, the same thing—seem to be on the retreat everywhere, people are looking for some way to hold on to what they believe America should be. I myself would be happy to see a conservative turn in the national moral landscape, regardless of peoples’ politics. Kevin DeYoung, a prominent theologian within the Evangelical movement, helpfully describes the appeal of Christian Nationalism against the backdrop of major social change:

“We have to realize that people are scared and discouraged. They see America rapidly becoming less and less Christian. They see traditional morality—especially in areas of sex and gender—not only being tossed overboard but resolutely and legally opposed. Of course, we should not give way to ungodly fear and panic. We should not make an idol out of politics. We should not fight like jerks because that’s the way the world fights. But people want to see that their Christian leaders—pastors, thinkers, writers, institutional heads—are willing to fight for the truth. You may think your people spend too much time watching Tucker Carlson, or retweeting Ben Shapiro, or looking for Jordan Peterson videos on YouTube, or reading the latest stuff from Doug Wilson—and I have theological disagreements with all of them (after all, some of them aren’t even Christians)—but people are drawn to them because they offer a confident assertion of truth. Our people can see the world being overrun by moral chaos, and they want help in mounting a courageous resistance; instead, they are getting a respectable retreat [from Evangelical Christian leaders, NJE].

Kevin DeYoung, “The Rise of Right-Wing Wokeism“

A confident assertion of truth. That is key. Christian Nationalism, in its various forms, is confident that it is right and is willing to stand toe-to-toe with the forces of cultural chaos, as it sees them.

The wise voice of the tradition

This is neither the time nor place for a robust discussion of Christian Nationalism. As I’ve mentioned above, it is a complex phenomenon with good, bad, and ugly motives and expressions. Having come this far in the post, I want to take a minute to converse with the voice of tradition which we stand in as First Baptist Church of Manistique. While our tradition does not answer all of our difficult questions about politics, it does give us some clear guiding considerations to help us in our disorienting times. As various voices clamor for some version of Christian Nationalism in an attempt to bolster up or recapture a culturally conservative America, we can ask some pointed questions drawn from our tradition.

How has Christian Nationalism worked in the past?

Baptists “came of age” in a time and place where the government sought actively to enforce some version of Christian values and church life upon all citizens. That is, most every government in Europe and in the American Colonies could be classed under some version of Christian Nationalism. And a lot of people didn’t like that. At all. Including lots of Christians who lived in those countries.

In fact, the modern, liberal form of government which we associate with the West rose partially in response to the devastating consequences of the wars of religion which shook Europe. Christians killing Christians in the name of Christianity.

While Christian Nationalism sounds like an appealing idea, especially when compared to the cultural chaos of the moment, we have to honestly acknowledge that it hasn’t worked well in the past. The historical record of countries where Christianity was politically embedded is quite terrible on a lot of fronts. When you mix politics and religion, you end up with politics. More on this below. That is one of the great insights enshrined in the Baptist tradition.

For a good contemporary example of the problems of religious nationalism, see the violent excesses of the Hindu Nationalist movement in India. For instance, consider the use of violence and social ostracization against non-Hindus to force conversions in the name of nationalism, or the increasing violence against any who report on Hindu Nationalism and religiously motivated violence.

Are the aims and values of Christian Nationalism Christian?

This question should always be on our minds whenever we see an attempt to mix politics and religion. One of the clear patterns of history is that when religion is a powerful social force people use religious language and symbols to achieve their own political ends (see next point). If we take a long and hard, or even short and cursory, look at Jesus in his ministry, one thing is evident: he did not organize a political force to take control of the government, the culture, or the world. He will do those things, in his own time, but it will be through his power as the Reigning King of the Universe, not through shrewd political machinations.

Are the aims of Christian Nationalism Christian?

That is a question which we must never stop asking. We can see from history that Christian Nationalism produces many social goods by enforcing a thin version of biblical ethics upon society. There is benefit there. But what Christian Nationalism obviously doesn’t do it build robust followers of Jesus. And, it is worth noting, it has not proven to be a sustainable model of society in the long run. The US Colonies and the Modern European Countries were all Christian Nationalist at one point. What happened? The very values needed to sustain Christian Nationalism grow up from people following Jesus, not from legislating morality.

The Baptist tradition also invites us to ask a more focused question about the role of the church in society. Is the church pursuing following Jesus, or is the church becoming enmeshed in trying to become the government? In a zeal to preserve vestiges of Christian culture from the ravages of militant “progressivism,” is the church living in such a way as to show hope and light of the gospel of Jesus to the world, or living in such a way to punch political opponents in the mouth? Attempting to force people to be Christian, or to live like it, never has worked in the past. Why would it now?

Do we suspect that we are being used for political ends?

Finally, dialoguing with the idea of the separation of church and state (and remembering that it arose out of a desire for Christians to not be forced to support other state churches), should alert us to the possibility that people may just use us for their political goals. In history, the church was intimately united with the state in the West. Why are some politicians interested in reviving this arrangement at the current moment? Might it have less to do with piety and theological convictions, and more to do with political power? That is always a concern to keep in mind.

Leaders can rise up and speak words that sound Christian for political purposes. Of course, there are politicians who are followers of Jesus. But when politicians speak the language of Christianity without actually showing a consistent devotion to growth in Christ-likeness, beware. As like it as not, they are trying to use the language of Jesus to gain earthly power for themselves—something which Jesus himself did not do. Remembering the tradition of separation of church and state serves to guard us from being swept away in the headiness of the moment.

Standing in our strength

The current interest in Christian Nationalism is complicated. There are many threads involved to consider in making sense of the tangled knot which we have. One thread we should hold to is the strong voice of tradition. Knowing the tradition in which we stand can help us ask important questions. Certainly, asking the questions doesn’t give us the answers of the good, bad, or ugly ways we can interact with the Christian Nationalist movement. As followers of Jesus, we need to be reminded that victory doesn’t come through politics. We serve a king who surrendered himself to an earthly government, yet who then, as now, is exalted over it.

How we vote or where our political allegiances fall will always be complicated. What our tradition helps us with, though, is to resist being drawn off course in our fervor for or against certain political events and movements. The course of a follower of Jesus is to follow Jesus. This may lead to places and governments that look decidedly Christian, or it may not.

In making these few remarks, I want us to see just how relevant even the preamble to our Core Beliefs is for us as we try to live together as followers of Jesus. There are lots of complicated forces pressing us in many different directions in life. These Core Beliefs, even if not always giving easy answers, at least can help keep us from being blown away by the storms around us.

January 15, 2023 Church Service

January 8, 2023 Church Service

Core Beliefs: Where are We?

Where are we? How can we tell? How can we know where we are going if we are not sure where we are?

As we begin a new sermon series looking at our core beliefs week by week, I wanted to reflect a little on the front end about the sermon series graphic that I’ve put together.

Since coming here to FBC Manistique, I’ve been making sermon series graphics. First, I’m not a graphic artist by training or disposition. While not unartistic, it is not an area of my skills which I have developed with any rigor. In fact, if anyone is gifted in the realm of graphic art, I’d be more than happy to engage your valuable services in designing sermon series graphics which can serve as a pictorial guide to engaging the sermon series.

This post is a reflection of what I am thinking in choosing this particular picture for the graphic for a series on our core beliefs.

An inheritance to stand on

As you can see above, the picture is of a person sitting on a lichen-covered rock up in a foggy, mountainous area.

Core beliefs are the firm and settled rock on which we stand. Core beliefs have to do with what we are certain of; the truths we base our lives on; the realities which serve as our firm foundation. They are solid. They are a rock.

We did not make up these core beliefs. While they are in some ways distinct to the particular church tradition that First Baptist Church happens to be in, within our core beliefs dwell the core teachings of the followers of Jesus across the millennia. They serve to sketch out the field and how we stand in it. They are solid.

An uncertain surrounding

But the most arresting part of this image is what you can’t see. The blanket of fog obscures everything else. The man in the grey-hoodie is on a solid rock, but we can only guess where he is in relation to anything else. The rock is firm, but the world is mist.

One of the difficulties which followers of Jesus are facing, and will continue to face, is that our surroundings are increasingly misty. It is getting harder and harder to locate just how the solid rock of beliefs we stand on relates to the rest of the world around us. Knowing the firm foundation even creates a bunch of further difficulties and questions that evade easy answer.

We live in a time and place which, to use a helpful scheme developed by Aaron Renn, is a culture that is hostile to the existence and message of followers of Jesus. I don’t mean by that to imply we face anything like the hostilities in many other countries of the world where Christians struggle and are persecuted. But what I do mean to imply is that holding the beliefs and values of followers of Jesus is increasingly looked upon as odd, socially backwards, and perhaps even threatening to the well-being of people and society around us. And, as a result, we are less certain how our solid rock relates to the world around us. We are increasingly wrestling with uncomfortable realities as our core beliefs become an island in the fog.

In a lot of ways, Manistique is a shelter from these broad cultural trends…so far. Who knows what the future will bring? It is shadows and fog.

Where are we?

What do we do in this situation? If I had a definitive answer to that, I’d happily share it—not to mention embrace it definitively in my own life. But I don’t have a definitive answer. We’re certainly not the first followers of Jesus in history to face the rolling fog enfolding our rock. Many real difficulties are here and coming. Yet, also, many opportunities.

One thing I am certain of: we must become more familiar with the rock we stand on. We must become more familiar not just with what we say we believe, not just with a set of social values generally conservative in nature, not just with an association to certain political movements, but an actual living and vital connection to the truths which have been passed down about who God is, who Jesus is, and the way that God’s spirit is at work in this world.

Our core beliefs are a touch point. They’re certainly not an exhaustive description, nor do they include everything that we need to stand and live and flourish, but they establish a core. And it is a strong enough core to answer the question “where are we,” even if we are never quite sure how that relates to the rest of the world. But, in a world of swirling mists, maybe it’s less relevant for us to be able to answer who other people are, and more important that we can show and say who we are; that we can display the truths which we stand on, live through, and live for.