Down the Rabbit Hole: redeeming the news, part 1

The news cycle is shorter than ever. That is commonly accepted wisdom (though it is debatable whether there is anything more worthwhile to say in the endlessly shortening news cycle or not). One easily gets the impression that the news is a track of sad music on endless repeat. Recently, I am reminded that the news is an endless rabbit hole that you can fall into and never come back out from.

The news

I used to not really watch the news. In addition to occasional online browsing, I would catch a few minutes of NPR here and there while driving the kids somewhere or commuting back and forth between my house and school.

But recently, I’ve felt myself falling down the rabbit hole of online news.

Online news

Since starting into pastoral ministry in January, I have tried to be more aware of what’s going on in the world. The stuff in the world and community weighs upon the lives of the people who live in the community, so it makes sense to engage with the news. But there is also a danger, which is what I have been noticing recently.

I have started to fall down the rabbit hole.

The rabbit hole

In the last couple weeks, I find myself with a nagging urge to go check the news. Have a couple minutes? Pull up the news tab. Need a break from thinking about the sermon? Go scan the news. And so forth. After finishing a chunk of work, rather than taking a couple minutes to stand up, walk around, and stretch, I find myself browsing news headlines.

Note, browsing headlines is not a very good way to engage with the news to begin with.

Since the headlines change by the minute—even when very little of substance changes that quickly—there is always something new to look at, read, be interested in. Sometimes there are stories that are worth reading. Sometimes there are stories which promise a juicy tidbit. For someone who has not watched an NFL game in I’m not sure how many years now, so far this season I’ve seen all sorts of headlines about Tom Brady’s life both on and off the field.

How does the rabbit hole draw us in?

The pull

I suspect the draw to go and check the news is much like the well-known and studied way that social media apps work. In short, social media platforms use algorithms. All that means is that they use complex mathematical rules describing how data relates to each other.

Check out here for a brief explanation of how algorithms work on various social media platforms.

Combining these rules, and the scads of information the social media company has about you, its user, results in you receiving a continuous stream of content directed your way that you should like to look at.

“Like” simply means content that the social media company believes you will take the time to look at, not whether you will find it pleasant, happy, or uplifting.

This all works on a pretty simple premise: our brains crave novelty. Said differently, we notice new things and tune out things that aren’t changing. Just think of the last time you walked into your favorite restaurant. When you first step in the wall of aromas envelopes you. Your nose is going wild as you soak up the delicious scents.

Within a couple minutes, you don’t even notice the smells anymore. But if you got up and walked into another restaurant, your nose would go crazy again. Why is this? Our brains prioritize paying attention to things that are new and changing, not to things that are staying the same. New stimuli—smells, sounds, images, touches—get high priority, but if the stimuli don’t change, in a short time they get downgraded and we no longer pay conscious attention.

Back to the digital world of social media and news. Online companies face one simple problem: the main way they make money is by selling adds, not by charging their users. In the online economy, you are the product. More pointedly, your attention is the product being sold by the tech company to an advertiser. It is in the tech company’s financial interest to keep you browsing as much as possible and coming back as often as possible.

The novelty-seeking brain is key. I want novel content. The news sites give endless novel content. Constantly changing headlines. The endless promise of something good.

Is falling into the rabbit hole good?

The dilemma

I‘ve been noticing that this increased intake of online news is complicated. On the one hand, I know much more about “what is going on in the world” than I have for quite some time. On the other hand, I’m not really sure that is a good thing. And I am not alone on this hunch.

It turns out, many studies note that watching the news can be deleterious to your health. Beyond the very real possibility that my stress (and yours, too) is heightened by watching the news, I wonder how all this casual news consumption relates to my ability to live well with the people I live with.

Staying out of the rabbit hole

In the next post, I reflect on some different things I am trying in order to put better boundaries around the news in my life. After all, as neat as it is to know things about what is going on all over the world, loving my neighbor as myself certainly should begin with my actual neighbors, not my digital ones.

October 2, 2022 Church Service

October 2022 Informer

September 25, 2022 Church Service

September 18, 2022 Church Service

Antichrist: the words behind the name

In certain circles, the nature and identity of the Antichrist exercises immense amount of interest, excitement, and speculation. I’m not writing here to talk about end times speculation around this enigmatic figure. Rather, I want to take a step back and consider the Greek word of relevance: ἀντίχριστος (antichristos). What does this word mean? More pointedly, I want to look at how our usage of “antichrist” in English obscures certain important facets of what this word means.

⚠️Reader beware: this post strays into what is called etymology—that is, how words are formed and why. Nothing too technical. You have been forewarned. ⚠️

On making up words

The word antichrist (Greek, ἀντίχριστος) is a Christian innovation. First John contains the earliest recorded use of the word and no one besides Christian authors bothers to use it after that. We can treat antichrist (ἀντίχριστος) as a brand-new word emerging in the particular social and religious context of early Jewish-Christian circles.

When John mentions antichrist in 1 Jn 2.18, he mentions a figure the readers are already familiar with. Both he and they already know what the word is intended to mean. This doesn’t help us that much in figuring out what John intends to communicate. In such a case, we can observe how the word is built (etymology) to help understand it.

There is a potential problem with this otherwise sensible procedure.

A problem in the prefix

The problem is straightforward: the prefix anti- in English is far more limited in meaning than the prefix αντι– is in Greek. Said a little differently: when we see an English word with anti- on the front, we have only one main meaning possibility; Greek words with anti- on the front had many more.

The venerable dictionary.com defines the English anti- this way:

a prefix meaning “against,” “opposite of,” “antiparticle of,” used in the formation of compound words (anticline); used freely in combination with elements of any origin (antibody; antifreeze; antiknock; antilepton).

The English anti- has one core sense: against. When we as English readers encounter the word “antichrist,” we only have one meaningful option for what we assume the word means: “against Christ.”

English borrowed anti- ultimately from Greek, but most directly through Old French and Latin. These borrowings only brought one nuance of the meaning of αντι- from Greek.

When we read “anti-” in “antichrist” we do so with blinders on because anti- only has one meaning. When we read ἀντίχριστος (antichrist) in Greek, the ἀντι- (anti) part has a variety of possible meanings.

Summary of the problem

When we read antichrist (ἀντίχριστος) in 1 John, we need to be aware of a couple things:

- it is a word made up for a purpose

- the parts of the word, while both meaningful in English, have a greater range of possible meanings in Greek than they do in English

In short, John’s reason for using the word antichrist may be lost in translation to us because the way our prefix anti- functions is much more limited than it was in Greek.

So, what does anti- mean, anyways?

As a Greek preposition, ἀντί does not really mean “against,” in the sense of “adversarial.” Here is a summation of its basic usages, from The Cambridge Greek Lexicon:

- referring to physical location: opposite (side of)

- referring to comparison or preference: equivalent to, in preference to

- referring to substitution: in place of, instead of

- referring to exchange of goods: in return, in exchange for

The Greek anti- relates two entities to each other in a variety of ways. At its deepest, most abstract meaning, it probably envisions two objects in space facing each other, say on opposite sides of a valley, wall, or tree. This basic idea extends through a variety of uses into meanings which are more specialized, but still involve relating two entities together in space, in valuation (more in a monetary sense), or in how they are esteemed.

👉As a preposition, anti- in Greek most basically refers to “against” in a spatial sense, not as an adversary.👈

There are Greek words where the sense of “against” as in “adversary” occur. The core idea of “against” each other in space naturally extends to a sense of adversary. Two armies who are opposite to one another in physical space are also in opposition to each other in metaphorical space as well. We see this meaning appear in words like (the hyphen makes clear the anti– part of the Greek word):

- ἀντι-λέγω “I contradict, speak against

- ἀντι-λογία “contradiction, dispute”

Summary: antichrist and the many meanings of anti-

In some Greek words, anti- means “against” as a hostile action, something like “in opposition to.” This is the portion of meaning that the English anti- comes from. However, this meaning is far from the only way that the Greek anti- worked in forming words. Consider this list of ways it is used to form words (taken from LSJ, a standard Greek reference dictionary). Anti- can mean:

- over against, opposite (spatial)

- against, in opposition to (adversarial)

- one against another

- in return

- instead of

- equal to, like

- corresponding, counter

When John’s Greek-speaking audience ran across the word “Antichrist,” had a variety of possible options of meaning for what that word might mean. We only have one.

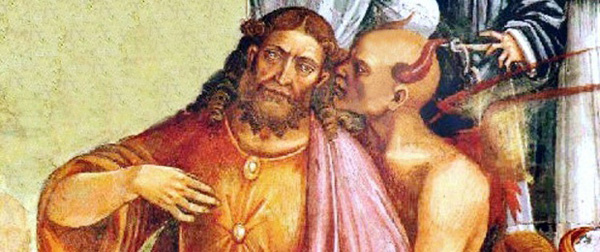

‘Antichrist’ as ‘substitute-Christ’

I want to suggest a broader nuance of meaning for the word “antichrist.” It does not only mean “against Christ.” It would be better to think of Antichrist as meaning something like “substitute-Christ, a counter-Christ.” The idea from 1 John and the other relevant NT passages (the man of lawlessness from 2 Thess. and the beast passages of Rev. being the most notable) is that antichrist is not just a person fighting against Christ; antichrist is a rival. Antichrist is like the leader of an opposite army and like a rival presidential campaign. Antichrist is not just fighting against Jesus, but is striving to achieve the same position as Jesus. Antichrist aims to be a substitute-Christ.

Being on the watch for antichrist is more than looking for pentagrams, Satan-worshippers, schock-rockers with bizarre costumes and make-up, or other things like that. “Substitute-Christs” come in all shapes and sizes. And a lot of those shapes and sizes look attractive within the church. Remember, in 1 and 2 John where the word “antichrist” occurs in the NT, the main concern is people within the church. The antichrists are those who deny Jesus as the Christ, which implicitly means setting up someone or something else in his place.

September 11, 2022 Church Service

September 4 Church Service

Enemies on the Journey Towards Joy

There are enemies on the road. If 1 John is a journey towards Joy, one of the things which will come up again and again is that there are enemies on the journey towards joy. Not all goes easy. Not every step is uncontested. In more conservative and evangelical branches of the church, we tend to have a heightened sense of the enemies on the journey. The enemy is the culture. “Those people out there” are enemies hindering our journey. Those policies, the loss of moral values, “people don’t go to church anymore,” the slide (or head-first, breakneck run) down into all sorts of depravity—those are the enemies on the way. And while that is true, an obsession with “those enemies” can blind us to what is probably the greater enemy: the person in the mirror.

A biblical scholar put it well when he said:

“Both the Old and the New Testaments make it painfully clear that God’s people are often their own worst enemies, worse by far than the “world” outside the church, when it comes to faithful appropriation of the gospel message.”

Walter A. Elwell and Robert W. Yarbrough, Encountering the New Testament: A Historical and Theological Survey, 3rd ed

The last part of the quote is key: “when it comes to faithful appropriation of the gospel message.” When it comes to living comfortable lives, then a changing culture is definitely a major enemy on the journey. To the degree we associate joy with what our culture calls “the good life,” to that degree changes in the culture hinder our joy. In our increasingly post-Christian culture, there are increasingly many ways that it is getting hard to be both a follower of Jesus and pursue the “good life” of the American Dream.

But…

Gospel Appropriation

Appropriating the gospel is a different concern. There are plenty of cultural hardships—and more appear to be coming—but these are not the only thing which keeps us from joy. The joy which is of highest concern in the Bible is a joy that can be experienced in want and in plenty, in persecution and in power. It is a joy that challenges many of our assumptions about how the world ought to work and many of the assumptions of what “the good life” is.

It is undeniable that there are many external enemies towards our joy.

But ask yourself this question: “What is hindering you from having the vibrant relationship with God that you desire?” While there are many factors hindering us, it is hard to conclude that outside influences have the ultimate say. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that my own lack of desire and engagement is the biggest hindrance in having a vibrant relationship with God.

Targeting the right enemies

We can address wrong beliefs. Those are an important and pernicious enemy on the journey towards joy.

We can address wrong actions. Those also are an important and pernicious enemy on the journey towards joy.

But it is difficult, if not impossible, to make advances when our attempts to address these issues aim mainly outward. The self rages against obedience to the gospel. The self hamstrings our own efforts on the journey towards joy by constantly directing our efforts in the wrong direction.

As we consider enemies on the journey towards joy, don’t forget that in many realms of life, you are your own worst enemy.