August 21, 2022 Church Service

Do What You Wish

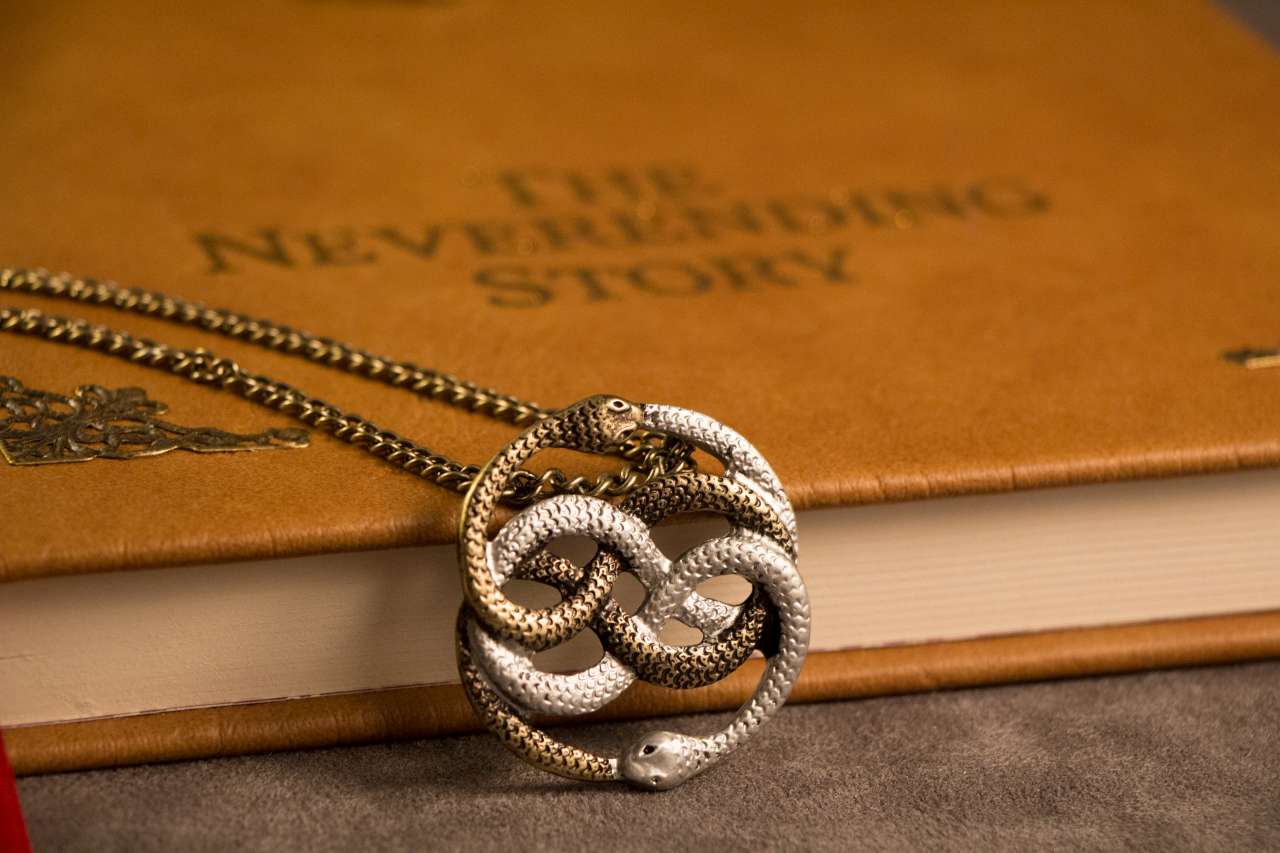

“Do What You Wish” (or, the original German, Tu Was Du Willst), is the message found inscribed upon the mystical medallion called AURYN in Michael Ende’s fabulous fantasy novel The Neverending Story (German, Die unendliche Geschichte). This mystical medallion plays a central role in the unfolding of the story as Bastian Balthazar Bux, the main character (more or less), enters the world of Fantasica and receives AURYN and its powers. For those interested in these types of stories, read this book. Sparing the details of how the story works, the phrase on the back of the medallion is intriguing: “Do What You Wish.” As the book unfolds, Bastian finds out that this seemingly obvious message is more complicated than it first appears. What you wish, it turns out, is not so easy to understand.

Check out Searching for Something for some more thoughts on the search for something everyone is on.

The meaning of “Do What You Wish”

In short, The Neverending Story plays on two related but distinct meanings of the phrase “Do What You Wish”: (1) do whatever you want or (2) do what you truly want. Bastian, on first reading the message, assumes it means (1) do whatever you want. He travels throughout Fantastica following his creative whims, making the world his own story however he pleases.

Each act of “doing whatever he wants,” though, steals a small part of Bastian away. He is rescued in the end when he finally learns that “Do What You Wish” means “you must find what you truly want and do that.” Finding what he really wants leads him back to the normal world, peace with himself, and a restored relationship with his father.

The Neverending Story is a clever fantasy retelling of the perennial story that finding what we actually want is counterintuitively more complex than merely following what we want.

What do you want?

What you wish for is not simple. In line with the recent sermon series The Word Still Speaks, I have been thinking about how God’s word relates to “what we want.” To put it into a question: do we engage with God’s word because that is what we want, or do we engage in God’s word as part of the process of finding what we most deeply want?

Neither of these is wrong but engaging with Scripture merely based on our whims is not a sufficient approach. In Scripture, God asks us to surrender in the most profound way: to surrender our (sense of) control over our own lives and instead move into the world that truly is, where God reigns and all things happen in line with his intentions. Even for those who have made the initial step in following God, this sort of surrender is often not enjoyable, not what we want in sense (1) from above.

When we think about engaging the Word of God—and all of life, really—we must be careful about how we look for “what we wish.” The easy and intuitive answer of “what I wish” to do right now may be, and often is, completely at odds with what you really wish in life.

At any given moment in life, most people would be able to answer the question “what do you want to be doing right now?” without a moment’s thought. As I am writing this, I would like to be sitting out in the beautiful sunny day. That is what I want right now, in the sense of (1). But going from one thing we want to the next in this way would resemble a cat chasing a laser dot in a hall of mirrors: something always looks worthy of chasing, but there is little hope of ever getting anywhere. Part of the journey into adulthood is learning the fact that we often must do something other than what we wish at any given instant.

But growing up in this sense doesn’t mean we ever learn to question why we wish what we wish.

Finding “what you wish”

The Scriptures work more on the sense (2) from above. It speaks to the “you must find what you truly want and do that” part of life. A key reality of God’s word is that it serves to guide our hearts to understand what is truly desirable. The more we surrender to God in his word, the more our heart opens up to realize what it truly wants but hasn’t been able to put into form.

Back in terms of The Neverending Story, each of us has a similar fate to Bastian. We embark on life, receive AURYN and its “Do What You Wish” message and have to figure life out. Finding that can be hard. Getting lost and distracted along the way is easy. It is easy to get so lost in “doing whatever I want” that we miss out learning what it is that our hearts really want.

One of the many ways God gives us to learn what it is that we truly wish is the Scriptures. The Bible intends to be the norming story of our lives. It lays down the guidelines and guardrails to lead us along. But rather than thinking of it as a book of rules for life (and it certainly has its share of rules), we can think of the Bible as a guide. Words whispered—sometimes shouted—from the heart of God to draw us back to him. Because only in finding our way to God can we learn to “Do What You Wish.”

August 2022 Informer

August 14, 2022 Church Service

Some Bible Reading Plans

There are many plans designed to help guide reading through the Bible. Anyone with a little time on their hands could come up with their own variants. Different plans have different advantages, so I will point three main categories to think about.

Check out this collection of reading plans. Not all the links on the page are current, but this gives you lots of good options and some ideas on what else to search for if you want something different.

Read the Whole Bible

The classic (for good reasons) approach to Bible reading is to move in a structured way through the entire Bible. Whether starting at the beginning and reading through to the end, reading in multiple locations each day, or any variation therein, these plans aim to engage the entirety of Scripture.

Common variations will involve reading through the NT at a faster rate than the OT, say 2x per year as opposed to 1x per year, or reading Psalms and Proverbs more often. Of course, you don’t need to follow a year schedule. But having a checklist to mark boxes off is really helpful.

The major drawback of such plans is that, for many people, the idea of reading the entire Bible through is quite daunting. It is a large book. If you don’t feel up to this yet, consider a couple other approaches.

Read Key Stories

Various plans focus on hitting the high points of Scripture. These plans take you more quickly through the main stories and events which help give the big picture into which everything else fits. A trip through a reading plan hitting the highlights of the Bible pays great dividends in coming to understand what is going on in this world and what is going on in God’s plan.

These sorts of plans are especially helpful for getting a big picture and, since they are selective rather than comprehensive, they are a less daunting way to get into the habit of regular Bible engagement.

Read Key Themes

Another way to engage with Scripture is through thematic readings. Many Bible studies and reading plans take a thematic approach. Want to know more about the Holy Spirit? What the Bible has to say about race? How to respond in times of personal crises? People have complied important passages into plans dealing with these and scads more topics.

Reading plans organized around themes can be found online, in tandem with a book study, or as part of a Bible Reading app.

On Bible Apps

There are lots of Bible reading apps. Far more than I have ever bothered to use, let alone look at. So I will just tell you here that the one I have on my phone is YouVersion. It is a good app with lots of different versions, a variety of built in reading plans and, one of my favorite features, many of the Bible versions even come with streaming audio! Want to read another language, or know someone who needs a Bible in a different language? YouVersion has thousands of language version available. And everything on it is freely available.

Personally, I still prefer to read my Bible as an actual book. The appeal of a codex has not worn off on me. But, reading (or being read to) on an app is a great way to help engage with Scripture.

Just Read Something

As a final plea, whether shooting for reading the entire Bible in a year, the NT in a year, or hitting the major stories of the Bible, just make sure you are shooting for something. Whether reading or listening, make sure you are engaging in God’s word.

Is New Testament Greek Precise?

Although I am a New Testament scholar of sorts, I keep in the background most of what I do with Greek. But, I want to share this recent article of mine for Bible Study Magazine, “Is New Testament Greek the Most Precise Language Known to Mankind?” It is a non-technical article about an issue which floats around in a variety of pulpits and Bible studies: the idea that Greek is super-precise in how it communicates.

I’m excited about it seeing the light of day. Check it out if it sounds interesting.

July 31, 2022 Church Service

July 2022 Informer

Meditating on Scripture

There are many reasons to talk about Scripture. Personally, I need regular reminders of the importance and benefit of engaging with Scripture. Like most healthy things in life, inertia kicks in over time and my practice starts to wear out. There is so much to do, things to read, good things to listen to and watch, and the primary easily becomes the secondary. This current sermon series, “The Word Still Speaks,” is in part a personal reminder to make the main things the main things. If Psalm 1 were to say that the blessed one meditates on Christian literature, or the most recent binge-watchable TV series phenomenon, then we would have more reason to get out there and engage with those things. But the path of blessedness is not in those things. So, here again is a short plan and plea to join in meditating on the Scriptures and to excel still more.

Meditating on Scripture 101: four steps

Here is a four step approach to Scripture meditation. These steps are easy and this is an easy place to start with meditating on Scripture. Although easy, the practice is deep and will grow with you and be able to sustain you into maturity. When Jesus compares the word of God to bread (quoting from Deut. 8.3), he gives an important image. Just as you never grow up to a point in life where eating becomes irrelevant, so too you never reach a point where chewing on the Scriptures is irrelevant. This practice of meditation, simple as it may seem, can (and should) become as central to your daily life and health as eating. While meditation is not a race, this practice can be done in 5 minutes.

What I am laying out here is my own version of what I was taught in seminary by Dr. Donald Whitney. He discusses meditating on Scripture, and many other valuable practices for spiritual health, in his book Spiritual Disciplines for the Christian Life. I recommend it.

Step 1: Read

Start with reading something in Scripture. We all probably should read more of God’s word than we currently do. That is a truism. But start somewhere. If a chapter a day seems too daunting, then start with a paragraph a day. If that is still too daunting, then start with 1 verse a day. You will not grow very strong on a diet of one verse a day, but the choice for one a day will be at least 365 days of spending time steeping in God’s word in the next year, which I wager is more than many of us have done this past year.

Start with something you can do rather than something grandiose. You will almost assuredly fail at a grandiose goal and then the sense of failure will hamstring your efforts and you will stop doing anything at all. So, start reading a manageable chunk of Scripture. Surely you can find space—make space—in the day to read one paragraph from the Scriptures. If that is more than you have been doing, then start there.

Step 2: Choose

Second, as you read through—whether it be one verse, one paragraph, or several chapters—pay attention to what strikes you. Now, I’m not suggesting that whatever sticks out to you in one reading of a passage is going to be the key to some profound and subtle understanding of a given passage of Scripture. That is not the point of starting out meditating on Scripture. We are working on chewing on the Scriptures as daily bread. Learning to engage with a 7-course meal is a different thing.

As you read, there is bound to be something in the passage that strikes you. Something in the text which presents a startling or comforting or challenging thought. Of course, you could use more elaborate methods of choosing a passage to focus on, and there is merit in that once established in meditation. But start where you are.

Step 3: Steep

Third, mull on the passage which stuck to you. The goal here is to go back to it and spend some time letting it steep in your mind and heart. What should you do? Here are a few suggestions:

- reread it several times (try putting emphasis on different parts of the verse)

- ask questions of the verse (you don’t need to answer them; the goal here is to spend time with the passage, not figure everything out)

- consider how it could impact your life today

Step 4: Pray

Lastly, spend a moment in prayer shaped by the truths you just focused on. Meditation should open up a conversation with God. After all, since the words come from God it only makes sense to speak with God about them

“Meditation must always involve two people—the Christian and the Holy Spirit. Praying over a text is the invitation for the Holy Spirit to hold His divine light over the words of Scripture to show you what you cannot see without Him.”

Donald Whitney, Spiritual Disciplines for the Christian Life, 55.

Step 5 of 4

The fifth step: repeat tomorrow.

Final encouragements

While meditation on Scripture is simple, it is not always easy. That’s ok. Keep at it.

Meditation is not a race! It is a time to find spiritual food for the day.

Photo by Ester Marie Doysabas on Unsplash