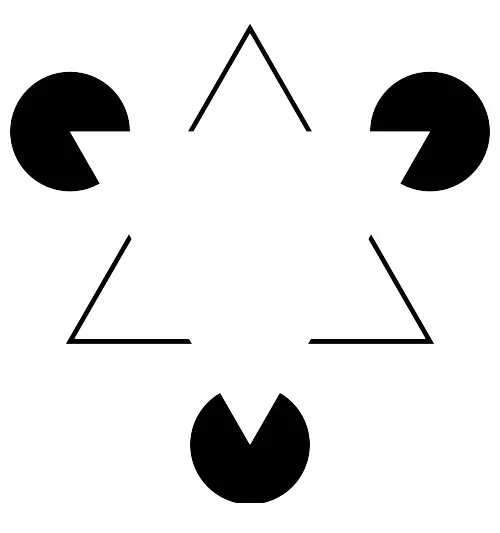

Go ahead and look at the following picture and count how many triangles you see in it.

Do you see two? Most people will see two at least. Maybe you notice that there are at least six little triangles in addition to the big triangles, which brings our total up to 8. Possibly you see 3 more triangles as the “Pacman” mouths. Which would give us 11.

Or maybe you notice that there actually aren’t any triangles in the picture.

This picture is an optical illusion, the Kanizsa Triangle, to be precise. Look closely and you’ll notice that there are no complete triangles anywhere in this picture. There are no lines that actually connect to form a triangle. However, your brain so desperately wants to hold them together that it is really hard to not see a triangle. We even generate lines in our minds that don’t exist in order to make the shapes relate to each other.

Making up the lines in the picture is a phenomenon researchers call the Gestalt law of closure. We tend to see objects that are close together as related group. It’s a useful trait in real life where things close together very often need to be understood in relation to each other.

Seeing may be believing, but believing is not seeing

Seeing is believing, as the old saying goes. Except sometimes, what we see doesn’t actually exist. Our seeing can be misled. Seeing is a reliable guide for a lot of life, but not all the time. We know this.

We also know that you can’t see everything you believe in. Sometimes it is just the way the world works. We don’t see air, or gravity, but we believe in them because of their effects.

I have never been to China, but I have zero doubt whatsoever that China exists. Not only is there all sorts of recorded evidence about China, but I know many people who testify that they are from China or have traveled to China.

We believe strongly in many things we haven’t seen, and many we will never see.

A different kind of seeing

Take a quick look at 1 Peter 1:7-9 (especially 8—9; 7 is there to make a complete English sentence):

7 These have come so that the proven genuineness of your faith—of greater worth than gold, which perishes even though refined by fire—may result in praise, glory and honor when Jesus Christ is revealed. 8 Though you have not seen him, you love him; and even though you do not see him now, you believe in him and are filled with an inexpressible and glorious joy, 9 for you are receiving the end result of your faith, the salvation of your souls. (NIV)

Peter, writing this letter, knew Jesus personally and had seen him after his resurrection from the dead (see 1 Peter 1:3). But the recipients of the letter hadn’t seen Jesus. And yet, with a glance of loving faith, they are able to believe and be filled up with the joy that Jesus provides: a belief-filled joy which pours out salvation to souls.

They come to see and know Jesus through the testimony of others, through the evidence of lives changed, and through their faith.

Our eyes are capable of “seeing” lines where they don’t exist in the above optical illusion. Our brains see the shapes and fill in the connections. The optical illusion just reveals to us how our minds engage with the world around us. Because in real life, seeing how objects close to each other relate is critical.

The life of faith is similar, in many ways. The eyes of faith are also capable of seeing see how people, objects, and events in the world around us relate together and point toward things that are bigger than we can directly see and know.

This passage in 1 Peter calls to mind an interesting quote from C. S. Lewis that I recently came across:

“I believe in Christianity as I believe that the sun has risen: not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else.”