March 27, 2022 Church Service

Part of the Stories with Intent series on Jesus’ major parables.

Do you want eternal life…or the Kingdom of God?

There are two types of Gospels. We call the first type the Synoptic Gospels. The Synoptic Gospels are Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Synoptic means something like “looking with.” We call these three the Synoptics because they look at Jesus in a similar way. This leaves the Gospel of John as the other Gospel.

In fact, only about 8% of the Gospel of John overlaps with the Synoptic Gospels. The chronology is different, the few events are different order, and the style of Jesus’ ministry is different. Rather than showing Jesus performing many miracles like in the Synoptics, John focuses in on 7. Rather than short teachings grouped together with stories, John is mainly comprised of long discourses of Jesus, often in ongoing discussion with Jewish religious leaders.

One difference of interest: eternal life.

Kingdom of God vs. Eternal Life

Matthew, Mark, and Luke characterize Jesus as teaching about the Kingdom of God (or the Kingdom of Heaven, in Matthew). The summary statement of his ministry is “repent, for the Kingdom is at hand” (Matt 4.17 and parallels).

In John, by contrast, Jesus regularly speaks about eternal life.

What are we to make of this? Did Jesus have two different ministries? Why are John and the Synoptics so different from each other on this point?

Two sides of the same coin

Before answering this, consider for a moment the following two statements:

- I am a Christian.

- I am a follower of Jesus.

What is the difference between these two? While the language is distinct and they certainly have different emphases, they are basically equivalent. I prefer the second expression to the first because I think the identity “Christian” has too much cultural baggage associated with it to be useful in many contexts. But, both expressions are essentially synonymous.

I contend that this is what we see in kingdom of God and eternal life in the Synoptics and John. Two different ways of expressing the same basic idea. And ways that would make sense to different sorts of people.

Kingdom of God and eternal life in the same context

Consider John chapter 3. In John 3.3 and 5, Jesus is talking with Nicodemus about entering the Kingdom of God:

3.3 Truly, truly, I say to you, unless one is born again he cannot see the kingdom of God.

3.5 Truly, truly, I say to you, unless one is born of water and the Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God

All well and good. This sounds like Jesus from the Synoptics. But note that as the conversation continues, suddenly the topic changes. In John 3.14-16 we read:

14 And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, 15 that whoever believes in him may have eternal life. 16 For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life.

In this one conversation Jesus and Nicodemus move from discussing entering the Kingdom of God to having eternal life without any obvious break in the discussion. This suggests that these two phrases represent the same basic idea.

This suggestion is confirmed in Mark 9.42-10.31 where we again see kingdom of God and eternal life occurring in close connection.

Mark 9.47: And if your eye causes you to sin, tear it out. It is better for you to enter the kingdom of God with one eye than with two eyes to be thrown into hell

Then again, the Rich Young Ruler comes and asks Jesus, “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” (10.17). In the follow up discussion Jesus has with his disciples, he tells them,

“29 Jesus said, “Truly, I say to you, there is no one who has left house or brothers or sisters or mother or father or children or lands, for my sake and for the gospel, 30 who will not receive a hundredfold now in this time, houses and brothers and sisters and mothers and children and lands, with persecutions, and in the age to come eternal life.”

In between those two mentions of eternal life, Jesus says this:

23 And Jesus looked around and said to his disciples, “How difficult it will be for those who have wealth to enter the kingdom of God!” 24 And the disciples were amazed at his words. But Jesus said to them again, “Children, how difficult it is to enter the kingdom of God!

The takeaway? The Kingdom of God and eternal life are two different ways of talking about the same central reality.

The Kingdom of Life, the eternal kingdom

There are a couple benefits from recognizing that “kingdom of God” and “eternal life” are similar concepts.

First, it helps us to see that although the Gospels are different from each other in a variety of ways, some of the differences are more cosmetic than actual. It appears that John, in writing his Gospel, used the “preacher’s prerogative” to shape his message to his audience. The language of eternal life requires less Jewish and OT background to understand what it means as part of God’s plan.

Second, it reminds us that the language and concepts we have for understanding humanity and God and the relationship we are created to have through Jesus is flexible. We are not stuck with just one idea.

Growing up, I don’t remember hearing much Kingdom of God theology, but lots about eternal life. I personally find “kingdom of God” more evocative and prefer that. Both are right ways to understand truths about what it means to follow Jesus. They bring distinct nuances.

As we think about our personal lives and about explaining and living gospel truths before others in our lives, it can pay to be flexible. We have more than one set of conceptual tools in our toolbox for understanding how we, and other people in our lives, are meant to relate to God in this life and in the life to come.

March 20, 2022 Church Service Video

Part of the Stories with Intent Series

Covid ministry reset

The “reset” wish

One common wishful dream busy people have is to be able to stop everything. Stop all the ongoing projects. Stop all the demands and the work and the pressures of life. To stop it all, and to relax. And even more than relax, we just want time to think about what we are doing and why. We just want a little bit of time to think and reflect and strategize about what we really want to be doing, how we want to be spending our time, where we’re putting our effort in life.

Churches have these same sorts of pressure. Churches, like any organization, have incredible amounts of inertia. Projects, programs, and patterns all just keep going because they have been going and because it takes more effort to stop them than to keep them going.

Inertia: projects, programs, and patterns

Organizational inertia explains the all-too common experience in churches where the on-going projects, programs, and patterns don’t fit the church we are anymore, but we have to keep doing them. Whether to keep the traditions, to keep the bylaws, or just to keep with the familiar, we keep on keeping on. Doubtless, there is some time in the past when God used and blessed the projects, programs, and patterns we are now doing. All the more reason to keep doing them. We expect that blessing to return.

I suspect the biggest reason why we keep doing the things we’re doing is because it takes more effort to change than it does to keep doing them. Change requires thought and effort and planning. And a good deal of risk. On any given week, we are already using up most of our thoughts and efforts and planning just keeping the projects, programs, and patterns going.

It is not bad or wrong to keep doing what we have been doing. But, if we have options and opportunities to think about it and change, it might be worth exploring.

The COVID reset

I suggest that churches in general, and FBC in particular, are currently going through the sort of reset which many of us so often long for in our personal lives. Thank you COVID. Or maybe, thank you God? Of course, the COVID pandemic hasn’t been (and still isn’t) full of leisure time to think and reflect. Mostly we were scrambling around trying to figure things out on the fly. But here we are. We’ve come through a year and a half, two years, of change.

As the COVID pandemic and the various restrictions that it has placed on corporate worship come to an end (Lord willing), what benefit is there in it? Does coming out of the COVID pandemic mean a return to business as usual?

Ministry as usual?

Business as usual isn’t wrong. But it also may not be right. Now seems like an ideal time for us to consider in both our corporate and personal lives whether business as usual from two years ago is worth going back to. Perhaps the last two years have showed us some new things, taught us some new values, and prepared us for different ways of living and doing ministry.

There’s certainly no virtue in changing and destroying things just because. But there’s also no virtue in continuing to do things the same old way just because. Maybe now is a good time to challenge our imaginations about what faithfulness as a church looks like in the world we live in now, not the world we lived in before.

For our sanity and for consistency, we need to come to a new business as usual. However, that doesn’t mean we need to have the same old business as usual. The COVID pandemic can be the opportunity we’ve needed for years—maybe not wanted, but needed—to prompt some introspection. In no particular order, here are some questions I have been prayerfully considering:

- Why do we do what we do?

- What are we trying to accomplish as a church, anyway?

- What could we do?

- What should we do?

- Why should we do it?

- How are we involved in discipleship?

- How are we thinking about the community that we’re serving in?

- What is the purpose of gathering together on Sunday for worship?

- What would be an ideal way to reach strengthen and equip people in our churches?

Seizing the reset

These questions, and many more, are worth asking. As business as usual becomes the norm again, it would be a shame if we passed up this opportunity we have been forced to have for the past two years. In this time, we have a God granted opportunity to ask ourselves if the business as usual we crave to return to is the business as usual that Jesus the Lord wants us to be doing.

March 13 Church Service

What is a good interpretation of Scripture?

A common question which arises in Bible study is: what is the right interpretation of the Bible? Dealing with parables at church recently provides a germane point to address this question. What is the “right interpretation”? And, if I did not understand the text the “right” way, does that mean I am “wrong”?

Followers of Jesus find in the Bible the words of God, the words of life. So we put a premium on understanding them rightly. The more time and effort we spend with these words, the more they impact our thinking and actions. It makes sense to be concerned with “right” and “wrong” interpretations.

Interpretation in a different light

I want to introduce the category of “good” and “bad” rather than “right” and “wrong.” While these two sets of categories share a lot in common, “good” and “bad” is a more flexible taxonomy. One of the benefits of thinking about interpretations as “good” or “bad” is that we can think about interpretations on a sliding scale.

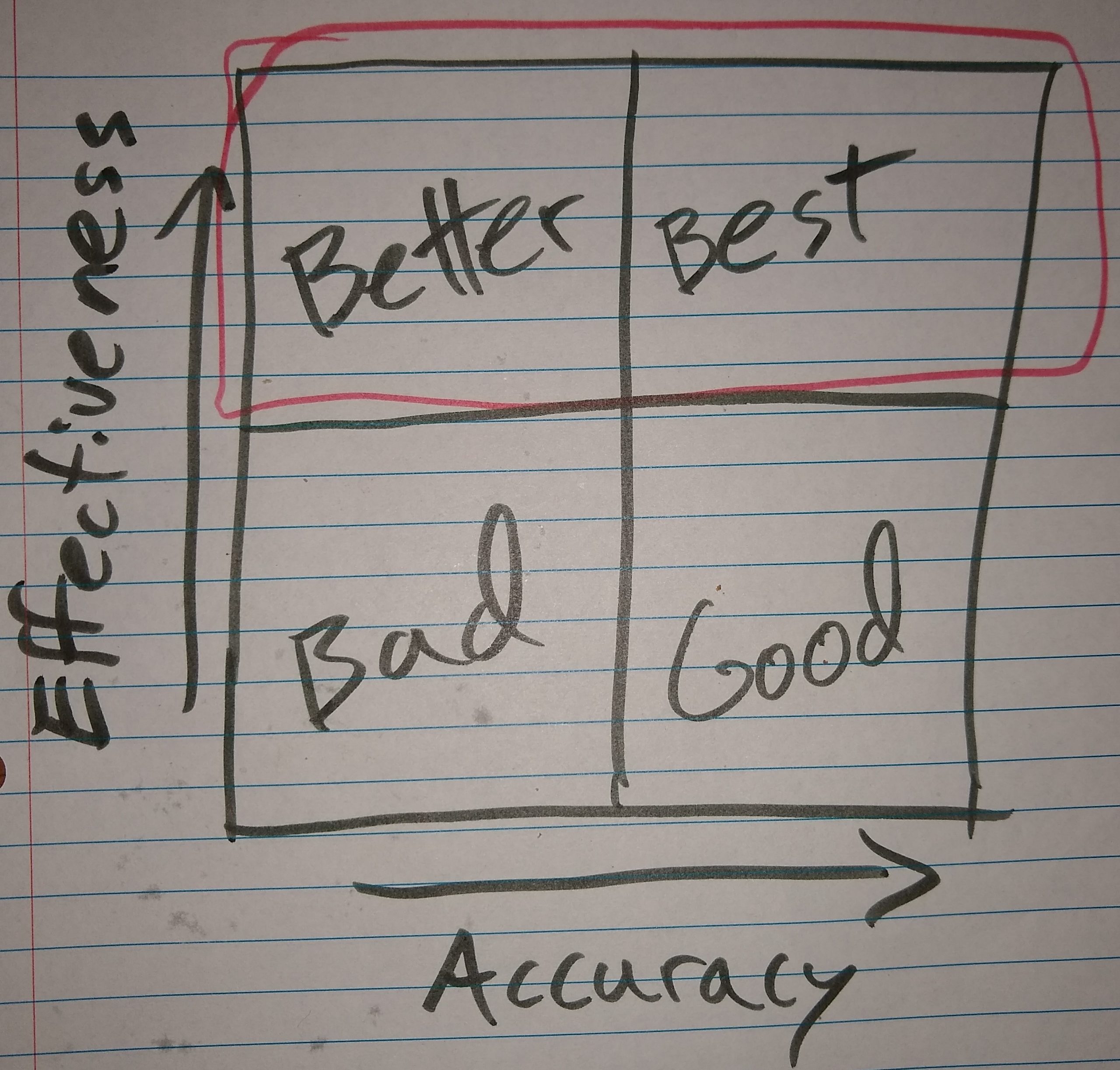

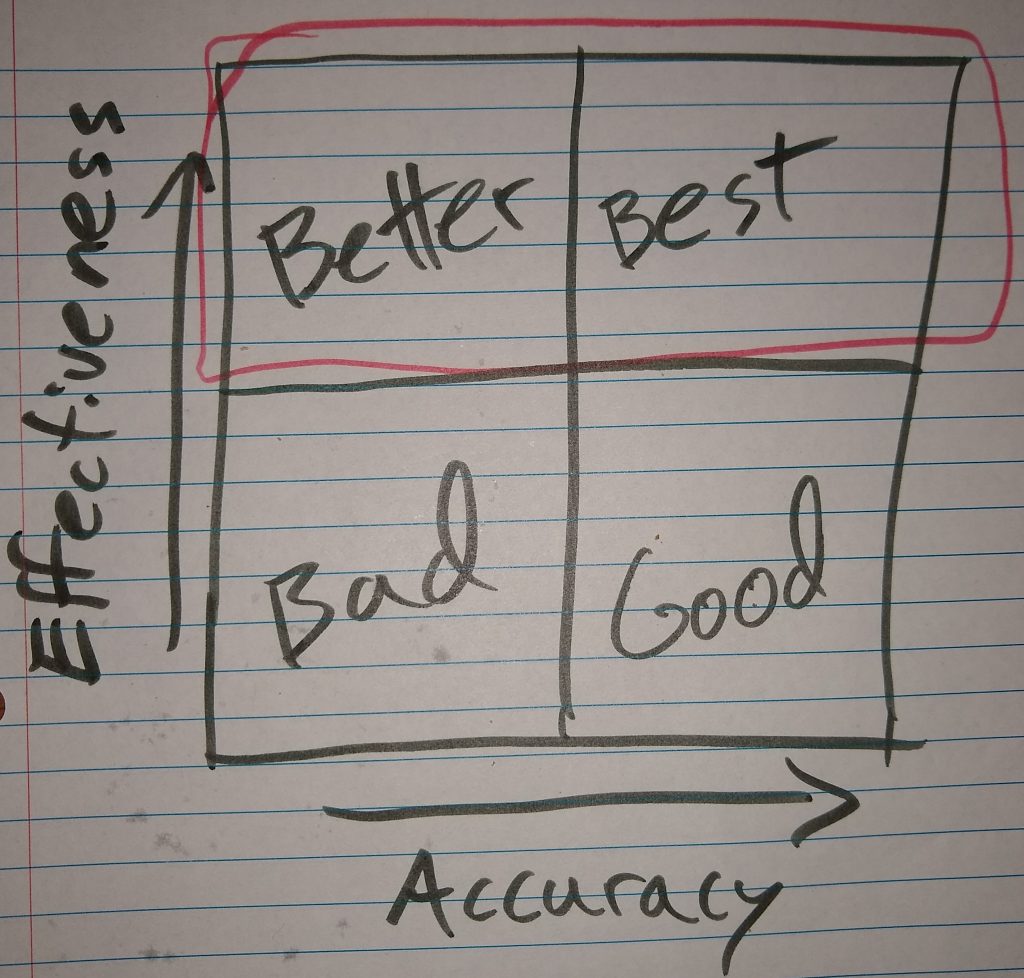

Consider the following illustration for a minute.

This typology of interpretations is simple. A lot could be said about it and about the thoughts behind it, but here I will offer just a few short comments. This 2×2 grid helps us think about the value of an interpretation.

On this 2×2, there are two parameters: accuracy and effectiveness. The obvious goal is for my interpretation to be both accurate and effective. Let’s briefly consider how this chart orients us to biblical interpretation.

Accuracy

By accuracy, I mean that the interpretation is plausible within the cultural, language, historical, literary, and theological context of the biblical passage.

One of my friends in high school cross country would chant Philippians 4.13 to himself all the time while running: “I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me.” While this verse is inspiring to cross country runners, dieters, and people changing habits the world over, those are all “inaccurate” interpretations of the text. In literary and theological context, Paul is not talking about being able to do “anything” through Jesus’ strength—like run a long way or loose weight—but about being able to bear up in his ministry in whatever situations he is in. This is a more accurate interpretation of Phil. 4.13 than as a promise that you can run a marathon, loose 20 pounds, or get up the courage to ask your boss for a raise.

The parameter of accuracy is the realm of interpretation associated most closely with academic work on the Bible: commentaries, original language study, literary analysis, historical backgrounds, and so forth. This aspect of Bible interpretation focuses on developing a more plausible understanding of any given passage.

Accuracy is important. But, accuracy is only part of the equation of good Bible interpretation. The second main component I call “effectiveness.”

Effectiveness

While accuracy is a part of any good attempt at reading and understanding communication, the parameter of effectiveness deals more closely with the nature of Scripture. God’s word is meant to be heard and to transform the hearer. St. Augustine of Hippo hit upon a helpful way to communicate what effectiveness in biblical interpretation entails. He writes:

“Whoever, then, thinks that he understands the Holy Scriptures, or any part of them, but puts such an interpretation upon them as does not tend to build up this twofold love of God and our neighbor, does not yet understand them as he ought.”

The basic insight is this: God has an intention for his communication in Scripture. God reveals himself with the intention of changing people who hear him. We are to grow in love for God and grow in love for neighbor. Augustine reasons that a good interpretation of Scripture is one that results in growing love for God and love for neighbor. After all, since that is the goal of God’s self-disclosure, it should be the result of rightly understanding it.

So what is a good interpretation?

This 2×2 graphic highlights the way the parameters of accuracy and effectiveness interact. The worst sort of interpretation is one that is neither accurate nor leads to growth in love for God and love of neighbor. An accurate but ineffective interpretation is better in that it at least understands the message of the text, even if the understanding does not result in any change.

I suggest that an inaccurate understanding of the text which results in effective life change in loving God and loving neighbor is better than an accurate but ineffective reading. Why? Because it grasps the big intention behind Scripture, even if it misses the details.

The best understanding is one that is both accurate and effective. One that both engages with and understands the message of the text in a plausible way and which directs the reader to deeper love of God and love of neighbor.

Hearing God in his word is meant to be transformative. There is much to commend in the saying—heard in many different forms and on many different lips—that the most important interpretation of Scripture is the one that you live. Accuracy safeguards the direction of our living and effectiveness refers to the motion in our lives toward God and toward others.

Pastor Nat’s Installation Service

Everyone is invited to the installation service for Pastor Nathaniel Erickson, which will take place on Saturday, March 27 at 6 PM at First Baptist Church. The event will also be streamed on the church’s YouTube page, which is accessible through our Livestreaming Page.

March 6, 2022 Church Service

Part of the “Stories with Intent” sermon series on Jesus’ major parables.

The guests at the parable of the banquet, part 2

In part 1 of this two-part post we revisited the Old Testament (OT), with a special focus on the difference between sin (narrower category) and impurity (broader category). Now we will take this background and use it to enlighten what is going on in Jesus’ parable of the banquet as found in Luke 14.

What does Jesus do?

With this paradigm of purity, we have a different set of concepts for thinking about the significance of what Jesus did in his ministry.

Let’s briefly remind ourselves of how the parable works. In Jesus’ story, the invited guests miss out on the feast because they don’t respond when it is ready. In anger, the feast-giver has his servants go out and bring in the “poor and crippled and blind and lame” to share in the feast.

This guest list is what triggers a connection back to the passage in Lev 21. When we read the parable as a transparent description of the question, “who will be at the feast celebrating God’s fulfilling of his joyous promises,” we find that the people there are the very ones excluded from access to the holy in the priestly service. This is surprising: the first shall be last and the last shall be first. Access to the holy is reworked in line with Jesus and his work, which shares both continuity and discontinuity with the Law from the OT.

This passage is by no means the only place such an emphasis appears in the Gospels. In fact, it is something of a theme running through Matthew, Mark, and Luke.

Jesus’ Table Fellowship

Jesus shared regular table fellowship with “sinners” and other social outsiders. This is part of where he got his reputation of being a friend of tax collectors and sinners.

In the ancient world, who you ate with had significant implications. Sharing a meal in someone’s house meant social acceptance of the other people with whom you were dining. One author notes:

“a scrupulous Pharisee would not eat at the home of a common Israelite since he could not be sure that the food was ceremonially clean or that it had been properly tithed”

Mark L. Strauss, Four Portraits, One Jesus: An Introduction to Jesus and the Gospels, 477.

Here we are with purity again. To remain ritually pure, and thus have symbolic access to the holy, required careful obedience. Since they could not control whether their host was doing the right things with their food, pious religious types only shared meals with others who were also pious on whom they could count to not bring impurity upon them through a failure to have ceremonially clean food.

Jesus’ table fellowship with sinners sets this view on its head. In fellowship with sinners Jesus was, of course, opening himself up to ceremonial impurity. What differed, though, is that Jesus came to bring access to God on a different plane. The coming Kingdom of God means free salvation to all who respond in faith. One might say that it brings open access to the holy that is no longer dependent on how pure/impure the individual is in their obedience to the Law. Jesus is able to “give purity” rather than to be defiled when he comes in contact with the impure. We see this, for example, in the way that Jesus heals people of skin diseases and raises the dead without ever becoming impure. Since Jesus has a super-abundance of purity, he is able to give it to all who will follow him. Therefore all alike, regardless of personal purity, are able to have access to the divine, that is, to God.

The Kingdom of God as restoration

One other point is worth brief mention here. On the guest list in Jesus’ parable are the blind and crippled. As pointed out in part 1, being blind and crippled was not in itself sinful. Though it results in being unclean for priestly work, it was not sin. However, during Jesus’ day we see evidence that thinking had developed linking physical ailments with sin. Consider the man born blind from John 9. The disciples ask Jesus,

“who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?”

The association is that the state of being blind—though not inherently sinful—was punishment for sin. Of course, there is precedent for this way of thinking in the OT, but the record is complicated. For example, Job was stricken with various ailments, but that was not related to sin. But King Uzziah was struck with leprosy (some sort of skin condition, which may or may not have been what we now consider leprosy) for transgressing his boundaries and approaching the holy even though he was not a priest authorized to do so (2 Chronicles 26). While the precedents are mixed it is easy to see how people would take God’s promises to bless and curse the nation based on its sin and individualize that (see Deut 28, for example). If God brings punishment such as plagues, difficulties in childbirth, etc. for the sin of people groups, then the sin of individuals must also be expressed in their physical circumstances in life.

This line of thinking provides a second helpful background for understanding Jesus’ ministry and the import of the parable. Jesus regularly healed people with physical ailments: blind, lame, crippled hands, etc. These were people whose physical circumstances would have (in the case they were from the tribe of Levi) rendered them unfit for access to the holy in priestly duty. They were also hindrances to participation in community life. They were also interpreted as symbols of God’s judgment for sin. Taken together, the blind, lame, and crippled were symbolic of the downtrodden and outsiders who neither had access to the goods of society nor access to the holy.

Jesus comes with a ministry of healing and restoration. Quoting from Isaiah, he describes his ministry as follows:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim liberty to the captives and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty those who are oppressed, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor. (Luke 4.18-19, ESV)

One of the ways in which Jesus demonstrated the Kingdom of God as restoration was in fellowshipping with and healing people whose physical infirmities placed them in various states of impurity, thus excluded from access to God, thus excluded from the expected blessings which God promised.

Tying it all together

Thinking about the parable of the banquet, we find that there is a multiplex of significance in the composition of the guests who end up at the banquet. More could be said on this front, as we have ignored the last stage in the parable where the servants go out to the hedges and highways to bring people in. The concept of purity turns out to be a helpful OT background for understanding why Jesus uses these categories as those who make it to the banquet.

The infirm map well onto the categories of priests who could not carry out temple work because their physical infirmities rendered them of insufficient purity to approach the holiness of God’s presence. The further theological implication that physical infirmity was tied up with sin added greater depth to the notion of people being impure. Jesus presents the very group assumed to be unworthy to enter into God’s presence as the one which gets to enjoy the joyous fulfillment of God’s promises to his people.

In Jesus’ parable, as well as in his ministry, he laid an example that access to the holy was being redefined in surprising ways. That is a call which we must never tire of hearing. In Jesus’ day, people who were certain that their approach to life was the one which led to access to the holy struggled with Jesus’ ministry. Jesus challenged them and pointed to a different way, as hinted at and promised in the OT—a way of faith and a way of God’s own making. Lest we be guilty of the same struggle, we must ourselves be aware of the human tendency to limit the path of access to God in ways that God doesn’t. We have a tendency to mix standards of our own behaviors and expectations in. We end up saying something like, “in order to come to God you have to do x, y, and z.” It is no coincidence that the steps we add tend to map onto the way that we live life.

Jesus is no more impressed by Christian versions of an “access to God through following prescribed purity codes” than he was of those of his day. While purity and holiness were and always will be important, Jesus challenges us to check where our hearts are at, because they can all too easily miss being at the place where God’s heart is at.