“Love” and “loving” feature prominently in 1 John. Love is a notoriously tricky word in English—we all know that “I love pizza” and “I love my family” don’t really mean much of the same thing at all. Many people in church are also aware that there are several different Greek words which are often translated with “love” in English (someday, I’ll probably rant about the many ways this is misrepresented). When we work with a slippery word like “love,” it is best to let the context we read it in show us what is meant. What we see in 1 John is that love—the sort of love which John is talking about—is a divine reality.

Who is loving?

One way to approach understanding “love” in 1 John is to pose a question: who is able to love? On the surface, this sounds like a silly question. Anyone short of a fully deranged psychopath can most certainly love in some fashion or another. But when we look closely at the way John talks about love in 1 John, we have to give a more careful answer.

As 1 John 3.14 puts it:

“We know that we have passed out of death into life, because we love the brothers. Whoever does not love abides in death.” (ESV)

We could look at many other ideas in 1 John, but a short summary is that the ability to love in the sense that John is talking about comes from being born of God. We come to learn what (this sort of) love is in the act of God sending his Son Jesus to the world (1 John 3.16; 4.10). This sort of love is both ‘from God’ (4.7) and in some sense identical with God (4.8, 16).

The (sort of) love highlighted here in 1 John is not a special quality of love. It is not as though followers of God have a level of love to give which is ‘more’ than other people. Indeed, there are many who reject Jesus in this world and yet certain portions of their lives are inspiring examples of giving up themselves for the good of others. What is special about this love is its source. The love 1 John highlights is love from God which those born of God have and those not born of God do not have. It is “divine” love, displayed in Jesus to the world. All those born of Jesus are born into this sort of divine love.

The answer to the question “who is able to love?” in the sense that 1 John is talking about is simple: followers of Jesus.

Love vs. hate

This insight helps to make more sense of the not-loving = hating equation throughout 1 John. If loving fellow followers of Jesus is a special capacity given to those born of God, then to treat others in any other way is to reject the very gift of divine love which has reached down to us in Jesus. We reject the gift by not extending it in our actions to those whom God has already extended it to.

One way to think about the sort of love which 1 John is highlighting is to think about giving people what they deserve. People deserve certain types of treatment from you. The exact way you were taught to treat other people varies, but people deserve certain levels of love in the sense of “generic-benevolence” because they are an important person in your life, a fellow member of your community, or just someone who happens to be in need. Acts of self-denying giving in these contexts are all good and they are fitting. God created us to live in relationship with one another, giving for the good of the other. But these acts are not what 1 John has in mind.

1 John focuses in on God’s special act of love, his choice of a people to give himself to in self-denying compassionate devotion so that they may benefit. Anyone can experience this love—you must be born of God. Having received this love and benefited from it, it becomes the pattern and model for the love we give towards each other. And, significantly, the family identity as children of God and the power of the Spirit within us empowers us to give this (sort of) love to each other.

Acting towards one another in ways that reject giving this sort of love, that is hate. It is hate because it is willfully choosing to reject God’s pattern of love for the family which he has already extended to us.

How to be loving

Love in 1 John is like a little piece of God planted into you. This seed of God is meant to grow and give a continual harvest of blessings towards other followers of Jesus and to the world.

While 1 John focuses mostly on loving other believers, the pattern of love we see in Jesus is a pattern extended towards everyone, whether they know and receive it and benefit from it or not (1 John 2.2).

Where to start? One of the wisest things to do is pray: Spirit of God, give me opportunities to be loving to others; show me how the love of God which is planted in me ought to be lived out day by day.

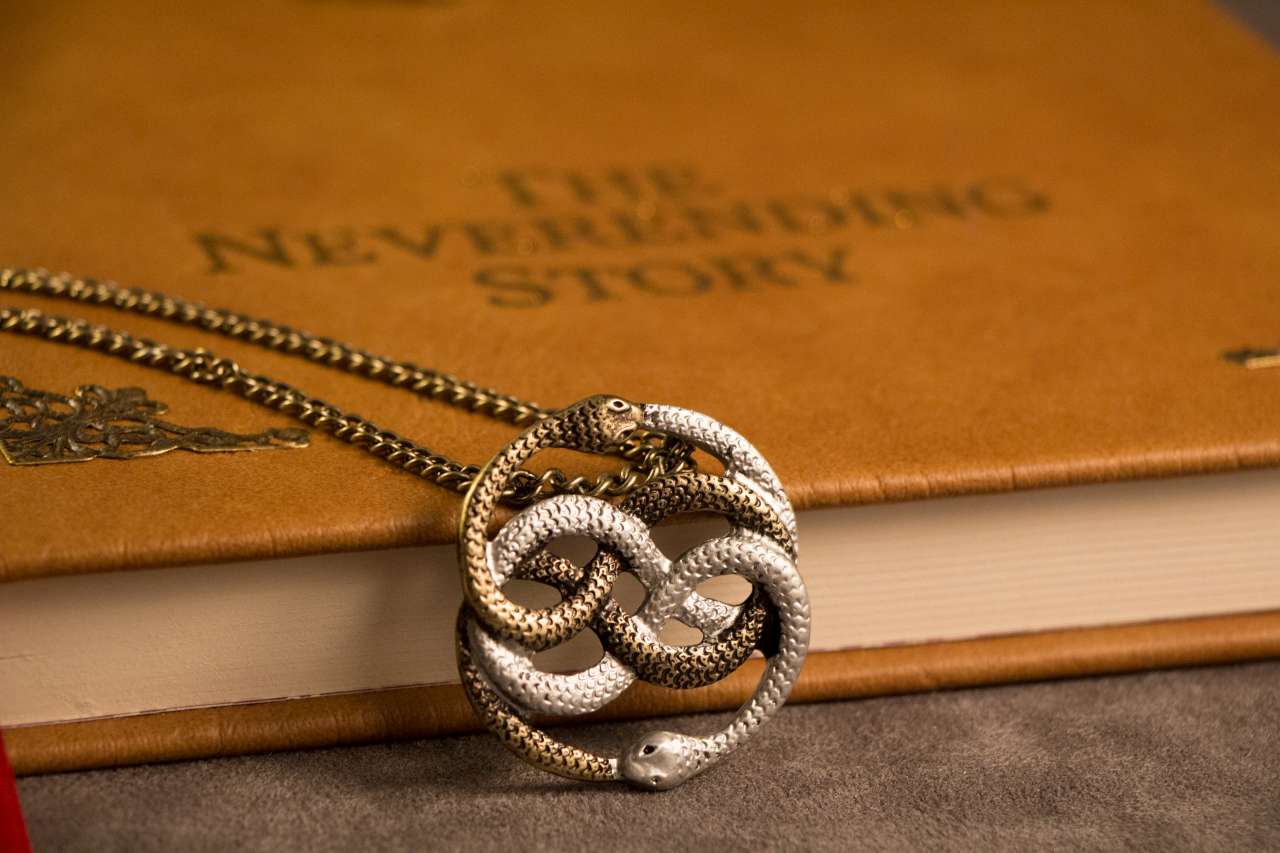

If you have ever seen the movie Pirates of the Caribbean (preferably the first one, which was a good movie, as opposed to the rest, regarding whose quality I raise profound doubts), you may remember that captain Jack Sparrow has a compass that is unique. It doesn’t point north. Instead, it points the way towards whatever your heart most deeply desires.

The Spirit of God in our lives is kind of like that. God’s Spirit continues to point the way towards the heart of God—and God is love. We need to get better at reading the compass points because they will always guide us to acts of love for others.