The Christmas Eve Candlelight Service is on for tonight at 7 pm.

The potluck tonight is on for 5 pm.

If you can get out of your driveway and have clear roads to drive on, come on out and join us for this special time of fellowship and worship.

First Baptist Church of Manistique

Friends pointing the way to a safe harbor through the light of faith in Jesus Christ.

The Christmas Eve Candlelight Service is on for tonight at 7 pm.

The potluck tonight is on for 5 pm.

If you can get out of your driveway and have clear roads to drive on, come on out and join us for this special time of fellowship and worship.

At the beginning of this Winter Reading Challenge, consider for a minute this question: Why read books? There are lots of reasons, some personal, some societal, some relational, some intellectual, and so on. Here are a couple thoughts about the role which reading can play in our lives not just as people who can learn from reading, but as followers of Jesus. Sometimes someone just says something well. Here I’ll pass on a few ideas about why to read.

Think for a moment about the way that good writers become windows through which we come to see things we did not see before.

“C. S. Lewis regularly emphasized that great writers sought to share something with their readers – something which they themselves had grasped or seen and wanted to pass on to others, so that they might benefit. The best writers are not self-promoting narcissists who demand that we look at them, but those who invite us to look through them at what they have seen, enabling us to share in their experience. They are thus windows to something greater. Lewis himself saw authors not as spectacles to be admired, but as a ‘set of spectacles’ through which we can look at the world and see it in sharper focus and greater depth.”

Alister McGrath, J. I. Packer: His Life and Thought, 2.

One aspect of good writing, especially fiction but also non-fiction, is that it provides an arena in which to challenge our certainties. Now, we must be careful. There are many things in life which we should be certain of and stand on. However, we are always in danger of becoming certain about what is merely our own limited vision of things. And when we become certain, we tend to demand others to live according to what we are certain is correct. This can cause all sorts of problems. Literature can bring us into another world and there unmoor us from what we were so certain about so that, when we come back to the real world, we are forced to ask questions of ourselves we would otherwise stay blind to.

“One aspect of this capacity to be multifaceted means that reading a good novel, or seeing a great play, we are conscious again of the complexity of human life, the ambiguity of so much behaviour, the mixture of qualities and motives in all of us. All this is a very healthy and important antidote to moralism. There is a human tendency to divide the world up into goodies and baddies. This can be so if religion is brought into it, though moralism certainly isn’t the preserve of religion. One of the great themes of Jesus in the Gospels is the way he tries to shake us out of all easy moralizing. We are directed to look at ourselves, at the great plank in our own eye before we call attention to the speck of dust in our neighbour’s eye. So literature, in bringing home to us the complexity, ambiguity and thoroughly mixed nature of human behaviour spells out and reinforces one of the central elements in the New Testament.”

Richard Harries, Haunted By Christ: Modern Writers and the Struggle for Faith, ix-x.

And finally, perhaps at the farther reaches of what literature does for us, is that it helps give us categories of thought and belief which make sense in a fresh way to us. It helps us to think about the questions of life we have in language that makes sense to us today.

“At a time when so much religious language has become either unbelievable or alien to many people it is in works of literature that we can begin to discover what the Christian faith is about and what is at stake.”

Harries, Haunted By Christ, x.

There are many wonderful works of literature and theology from years gone past. Being a fluent and dedicated reader requires at least periodically venturing into the great tomes of bygone years. Yet, even spending a short amount of time in a book of a different century often feels like venturing into a foreign land. While the great authors of the past are writing about universal human issues, they do so in a way that often is foreign to us. Indeed, sometimes so foreign that it evades our understanding entirely.

In a similar manner, sometimes the religious and moral answers to life’s questions which we rely on belong to a different dialect, a different time and place, and have lost some of their forcefulness. Literature can shake up our thinking and help us keep speaking the language of our hearts in this day and age, rather than the language of peoples’ hearts from 100 years ago.

Finally, and related, literature is one of the means we can become aware of the ways Christ minsters to us in this time and place, and the ways we need to be broken out of this time and place:

“To every age Christ dies anew and is resurrected within the imagination of man. This is why he could be a paragon of rationality for eighteenth-century England, a heroic figure of the imagination for the Romantics, and exemplar of existential courage for writers like Paul Tillich and Rudolf Bultmann. One truth, then, is that Christ is always being remade in the image of man, which means that his reality is always being deformed to fit human needs, or what humans perceive to be their needs. A deeper truth, though, one that scripture suggests when it speaks of the eternal Word being made specific flesh, is that there is no permutation of humanity in which Christ is not present.”

Christian Wiman, My Bright Abyss: Meditation of a Modern Believer, 11.

To live now means to be hyper-aware of certain realities of the human experience and to be hyper-blind to others. There are whole ranges of the human experience which we see as half-shadows, or in various degrees of light. The first way we turn to Christ for rescue is doubtlessly in terms of one of the hyper-aware realities of human life in this day and age. Those are the types of brokenness which constantly smack us in the face. But Jesus came to rescue and restore not just those aspects of human life which our day and age lionizes. He came to redeem humanity in its totality, with all its endless complexity.

Reading can help us see the depth, the greatness, the height, the bigness of just what it is that God is doing in restoring the world through Jesus. And to see how he is doing that in our lives.

Happy reading, and may your journey through books bring you to places you never would have dreamed you could go, but to the very places your heart has always been restless to find.

Why does Christmas involve so much stuff? I suppose where you are in life, especially regarding whether you have younger children or not, or grandchildren, presses this question more or less into your psyche at this time of year. But why does Christmas have so much stuff?

One could go on an endless rant, site endless studies, give endless statistics about the amount of stuff at Christmas time. I just wanted to briefly share thought provoking comments I came across the other week in thinking about this question.

I find great resonance with the thoughts of this writer, who says:

“The question for me is: how do we confront the dichotomy between the true meaning of Christmas and our learned behavioural norms? I know my two young children have enough – more than enough – of everything. Even they think they have enough. However, ingrained in my psyche is that Christmas morning should herald a lounge bursting with gifts and stockings that take the whole morning to open. If the most sustainable choice is a gift not manufactured, not transported, not purchased, not wrapped, not opened, not sent to landfill, or discarded in some toy box, why do I seek to find ways to fill up my children’s Christmas lists?”

This writer mainly has issues of environmental sustainability in mind. I share these concerns, to a large degree, but I also struggle over questions of materialism, greed, entitlement, the deadening effect material plenty can have on the soul, and the good old fashion desire to just have less junk in the house to have to deal with.

I wonder just what it is that makes it so hard to change. There are so many desirable reasons to be less involved in “stuff” around Christmas time, and most people could cite a good many of the reasons, but the stuff train keeps on rolling. Why do we often feel powerless to do anything but pass on to our children/grand-children the same as we received, even when we are uncomfortable with it and see problems in our own ways of living?

Maybe the difficulty is that stuff is so ingrained as part of life that it blinds us to its idolatrous influence in our lives. Maybe.

Consider today Jesus’ words of caution to two brothers arguing with each other about their inheritance:

Take care and be on your guard against all covetousness, for one’s life does not consist in the abundance of his possessions. (Luke 12.15 ESV)

I doubt I’ll ever have an answer to these questions that feels right. But I’m dedicated to trying to chip away bit by bit at the materialist/consumist streak which runs through my heart. Indeed, if we ever get to a point where our hearts are comfortable with what is one of our culture’s greatest and most obvious sins, then we have lost a key part of the faithful life and prophetic voice we should have as God’s people living in light of KOG values.

Christmas time is a good time to talk about generosity. In fact, it is probably the best time of the year to talk about generosity since most people are in a more generous mood around this time of year—or are trying to coach themselves into feeling more generous. Perhaps it is nostalgia, perhaps people fear Ebeneezer Scrooge’s fate, or perhaps it is the time of year many set aside to experience joy in giving to others. Some are doubtlessly moved along on the binge-purge cycle of guilt and give generously to make space for a new load of stuff anticipated to arrive over the holiday season. Whatever the case may be, there is benefit in thinking a little about generosity and what it is.

In our recent trip through the book of 1 John, we came across this zinger of a verse:

But if anyone has the world’s goods and sees his brother in need, yet closes his heart against him, how does God’s love abide in him? Little children, let us not love in word or talk but in deed and in truth (1 John 3.17-18 ESV)

This verse raises difficult questions fir a relatively wealthy society about wealth and poverty. A larger amount of people than at any other point in recorded history “have the world’s goods” and are not in obvious need (though let us never forget the many people around us who are in need, even if we don’t see it). Rather than tackle the whole, complicated topic of wealth, poverty, and generosity from a biblical perspective, I want to highlight some interesting work on generosity from Thrivent Financial, in partnership with the Barna the research group.

In the church world, people are often familiar with the idea of tithing. Tithing refers to the practice of giving 10% of your income, generally to church. It is rooted in the Old Testament Law given to the nation of Israel (though, in practice, it seems that ancient Israelites gave a good bit more than 10% in mandated offerings). Tithing is just one of many ways that people in churches talk about generosity through financial gifts. In fact, for many in the church context, the language of generosity is the language of finance.

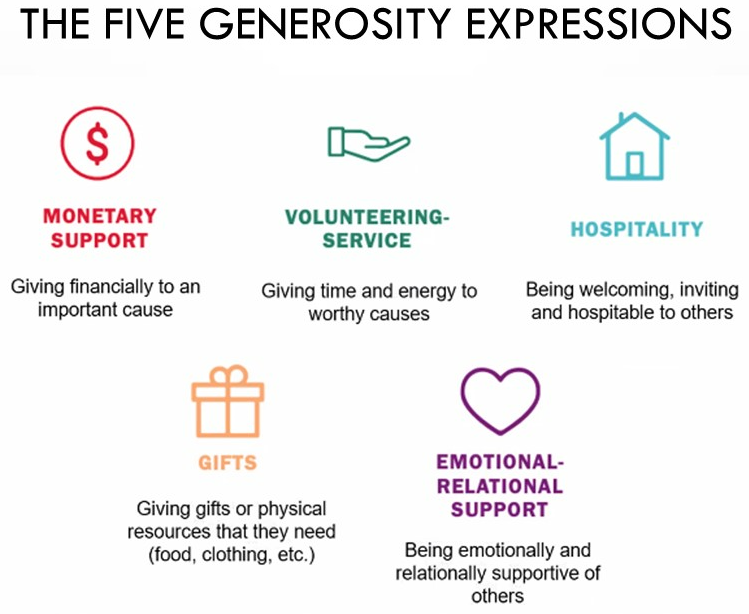

Rather than talk just about giving money—which is certainly an important part of the picture of generosity—let’s think about generosity through the perspective of Thrivent Financial’s innovative Five Generosity Expressions.

Here they are:

Thrivent developed these helpful five categories as a way to describe how people give and receive generosity.

Take a moment and ask yourself the following questions:

A robust, biblical picture of generosity certainly involves what we do with our money. But these other facets of generosity are not to be discounted.

From a strictly biblical perspective, I would be inclined to say something like this. Monetary support and Gifts closely correlate to the biblical idea of “giving alms.” That is, people giving money to care for the needy, to provide opportunity for those without it, and so forth. The other categories of generosity which Thrivent develops could be wrapped into a larger category: living in community. They are the sorts of ways that people can and do bless each other in acts of service and relationship.

During Christmas time, maybe take a little time to consider what people you know that are operating at a low ebb and could benefit from a visit, or thank you, or an invitation out. And think about being generous in this way not just as something to “throw in” during the Christmas season. If you are like most people, throwing much more in this time of year may result in a mental breakdown.

Instead, think about how over the course of the coming year you can be generous with your time, presence, and emotional-relational support to some people who could use it.

People often call Jesus “the greatest gift of all.” And that is true. As you consider being generous and different ways to be generous, consider that God’s generosity meets people in all areas of life, and in all the messy needs of life, not just the ones that we can write checks to help with

This is part 2 of a 2 part series on why so many translations. This series began life as a Sunday School class, so if you were there, much of it will be familiar. Part 1 began by introducing some important ideas to help us better understand why different Bible translations end up being different from each other. In Part 2, I consider some more of the reasons why there are many translations, as well as work through 3 case studies to illustrate how different decisions and practices by translators work out in real translations. You can check it out here:

Which translation is the best and which should you use? My short answer–read the whole thing for a longer answer–is that there are many good ways to engage the Bible. All translations make trade offs, none is perfect, but most are good at doing what they do.

Advent is coming! *

Advent is a Christian tradition stretching back into the early church. It marks out a time to prepare for the high celebration of Christmas. In Advent, we look backwards at the promise fulfilled in the coming of Jesus. At the same time, we look forward to the Advent of Jesus yet promised, when he returns to complete the rescue of all things and reign in an eternal kingdom.

Check out this helpful description of the origin and development of Advent as a Christian celebration.

We will walk through Advent at church this Christmas season. For added depth to the experience of rejoicing in the Advent and longing for the second Advent of Jesus, consider following along through the Advent season with an Advent reading plan. There are thousands out there which people have put together. Some are a few days, some are weeks long.

If you use a Bible app like YouVersion, it probably has a selection of Advent reading plans built in!

I’m including here an Advent reading plan that will take you through the 28-day journey from Nov. 27 through Christmas Eve. Join in the time of preparation and longing this Advent season.

Since “Advent” just means “coming,” this statement is kind of a highbrow joke.

How good are you at inspecting fruit? No, I don’t mean your ability to pick out a watermelon at the grocery store that is at peak ripeness and not yet going bad. Nor even whether or not you can handle commercial fruit packing. I spent a summer working in a blueberry packing shed doing commercial fruit packing. You quickly develop an eye to notice a bad berry in the midst of a sea of good berries slowly crawling by on the conveyor belt. The most stressful times where when the inspectors would show up to check the quality of the blueberries going out. Each pint of blueberries is only allowed to have so many non-optimal berries—still a little green, a little past ripe, etc. Whenever the inspectors showed up, suddenly the sorting lines needed to go extra slow and everything needed to be done extra carefully. While no one does a perfect job at inspecting fruit like this, you can be thankful that it happens; the fruit you get to buy at the grocery store is better for it.

Inspecting fruit for eating is useful, but I’m thinking more about fruit inspection in the sense that Jesus talks about in the Sermon on the Mount. In Matthew 7.15-20, he puts it this way:

15 “Beware of false prophets who come to you in sheep’s clothing but inwardly are ravaging wolves. 16 You’ll recognize them by their fruit. Are grapes gathered from thornbushes or figs from thistles? 17 In the same way, every good tree produces good fruit, but a bad tree produces bad fruit. 18 A good tree can’t produce bad fruit; neither can a bad tree produce good fruit. 19 Every tree that doesn’t produce good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire. 20 So you’ll recognize them by their fruit. (HCSB)

The image here is clear—good tree gives good fruit, and so forth. But what is good fruit? And what is bad fruit? Within this parable, there is no definition of what sort of fruits in life are good or bad. We have an intuitive sense of what good and bad fruit in peoples’ lives must be, but are those intuitions right? Maybe we have become a little sub-optimal as fruit inspectors because our apprehension of what makes fruit good or bad has gotten a little skewed.

Over this past year, I listened to a significant podcast from Christianity Today called The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill. It is a long form journalistic investigation into the rise and fall of Mars Hill church out in Seattle. In general, I stay away from the world of celebrity pastors, but when I saw this production voted as one of the 10 most significant Christian news events of the year, I thought it would be worth checking out. And it was. One question which came up over and over again in many different forms throughout the podcast is this: has the evangelical church in America become confused about what good fruit is?

If you glance back at the passage above from Matthew, note that it is a warning about people coming into the church who look and talk like they belong there, but who are really wolves. It is not a warning to avoid whackos and nut jobs; rather, a warning to avoid intelligent, savvy, charismatic leaders who, on first (and second, and third) glance look like just the kind of people who should be leading churches, bible studies, and ministries of any sort. These are the sorts of people who get resourced, who become famous, who become influential, who move audiences, who move product. But, they may not be the best people. The fruit that they bear may not actually be good fruit. Maybe we just fool ourselves into thinking that results must be good fruit.

Maybe we are so hungry to see fruit of any sort, that we don’t really care to look carefully and judge whether the fruit is good or not.

Within the context of the Sermon on the Mount, I must conclude that the good fruit Jesus has in mind is the pattern of life and obedience which he is laying out in the sermon. In other words, the good fruit we should look for in the lives of leaders and influential people—as well as in our own lives—is primarily a set of character traits that we might sum up under the term “Christlikeness.”

We are all involved in following other people. Many other people speak into our lives about how to live and who we should be—by words or actions. A central skill for us to develop is “fruit inspecting.” There will be many people who step into our lives claiming they know the path towards the good life. To decide whether they are worth listening to and following requires some fruit inspecting. We should be watching for people whose lives show growth in Christlikeness—the fruit which Jesus calls good—and follow along with them. No one this side of eternity will get it all right. But we can look for others who are walking in the right direction and walk with them.

Have you ever felt decision fatigue considering what English Bible to read? Or found yourself wondering, “If there is only one Word of God, how come we have so many translations?” If so, you are in luck! Here is the first part of 2 parts of written up notes from our 2-week class on why there are so many English translations–and which ones are good ones to use.

For those who were there, there is more information here than we covered in class. For those not there, here is a long (and probably more boring) version of what we talked about in class.

Part 1 describes some of the history of English Bible translations, along with introducing some important ideas to help us better understand why different Bible translations end up being different from each other.

Stay tuned for Part 2 in the not-too-distant future.

1 John 4.6 ends with a sentence translated variously in English:

The first element of the two is pretty solid—Spirit of truth. But there is a little difficulty when it comes to handling the second part: deception, falsehood, deceit, error. While all related, these words convey various distinct ideas. What is going on here?

Summary: the idea here is not a spirit who is true vs. a spirit who is in error; rather, the spirit of truth is the spirit which leads God’s people to remain in all things from God and the spirit of deceit/deception which aims to bring people to evil, blasphemy, and apostasy.

In Greek at large, the word here translated ‘error’ or ‘deception,’ planē (πλάνη), generally means “going astray, error.” It is related to the word from which we get our word planet. Without a telescope, planets look like stars. However, they behave quite perversely—they ‘wander’ around in the night sky. The Greeks named these celestial bodies “wanderers,” as in, “stars which have gone astray/wander.”

Our word of interest, planē, usually does not indicate a malicious intent. That is, a “spirit of error” would generally mean a spirit that is astray, rather than one whose nature and aim is to lead others astray.

If general Greek were all we had to go on, this would be the end of the discussion. However, within the rich tradition of Jewish and Christian writings, we see another, more specific usage emerging.

The Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs is an interesting work, written mostly before the New Testament. It is mostly a Jewish work.

I say mostly because, like many Jewish works from antiquity, its exact date of composition is not known (and possibly different parts come from different times) and it was transmitted almost exclusively by Christians for use by Christians. In transmission, some people could not resist adding explicitly Christian ideas here or there into the work.

It is interesting for a variety of reasons, but most notably because it includes several uses of this same expression in Greek—“spirit(s) of planē.” This expression occurs at least 13x.

Within these various passages, we see that “spirits of planē” means something more than just spirits that are wrong about something. Instead, “spirits of planē” refers to Satan and his spirits who tempt people to evil, blasphemy, and apostasy.

1 John 4.6 ends saying, “from this we know the Spirit of Truth and the spirit of planē.” We have good reason to suppose that planē here refers to the spirit of antichrist, namely the spirit of Satan. This is a spirit of deception as opposed to the Spirit of truth. The idea is not that there are two spirits, one true and the other in error, and we get to choose who to follow. The picture here is actually more like shoulder angels from the world of cartoons.

We recognize the Spirit of Truth and the spirit of deception by how they relate to Jesus Christ come in the flesh. The Spirit of Truth leads people to Jesus and enables them to hear his voice. The spirit of deception leads people away form Jesus. In the context here in 1 John, it is a subtle leading away. It is not a frontal assault on all that is good and godly, but a continued practice of deception calculated to lead followers of Jesus away to become followers of antichrist, the replacement Christ, the enemy of God.

This passage is just one of many facets of 1 John which call for followers of Jesus to be active in following the “good shoulder angel,” the Spirit of Truth, and warning them that the “bad shoulder angel” is real and is actively involved in trying to deceive people and lead them astray. Neutrality is not an option; you follow one or the other.

“Love” and “loving” feature prominently in 1 John. Love is a notoriously tricky word in English—we all know that “I love pizza” and “I love my family” don’t really mean much of the same thing at all. Many people in church are also aware that there are several different Greek words which are often translated with “love” in English (someday, I’ll probably rant about the many ways this is misrepresented). When we work with a slippery word like “love,” it is best to let the context we read it in show us what is meant. What we see in 1 John is that love—the sort of love which John is talking about—is a divine reality.

One way to approach understanding “love” in 1 John is to pose a question: who is able to love? On the surface, this sounds like a silly question. Anyone short of a fully deranged psychopath can most certainly love in some fashion or another. But when we look closely at the way John talks about love in 1 John, we have to give a more careful answer.

As 1 John 3.14 puts it:

“We know that we have passed out of death into life, because we love the brothers. Whoever does not love abides in death.” (ESV)

We could look at many other ideas in 1 John, but a short summary is that the ability to love in the sense that John is talking about comes from being born of God. We come to learn what (this sort of) love is in the act of God sending his Son Jesus to the world (1 John 3.16; 4.10). This sort of love is both ‘from God’ (4.7) and in some sense identical with God (4.8, 16).

The (sort of) love highlighted here in 1 John is not a special quality of love. It is not as though followers of God have a level of love to give which is ‘more’ than other people. Indeed, there are many who reject Jesus in this world and yet certain portions of their lives are inspiring examples of giving up themselves for the good of others. What is special about this love is its source. The love 1 John highlights is love from God which those born of God have and those not born of God do not have. It is “divine” love, displayed in Jesus to the world. All those born of Jesus are born into this sort of divine love.

The answer to the question “who is able to love?” in the sense that 1 John is talking about is simple: followers of Jesus.

This insight helps to make more sense of the not-loving = hating equation throughout 1 John. If loving fellow followers of Jesus is a special capacity given to those born of God, then to treat others in any other way is to reject the very gift of divine love which has reached down to us in Jesus. We reject the gift by not extending it in our actions to those whom God has already extended it to.

One way to think about the sort of love which 1 John is highlighting is to think about giving people what they deserve. People deserve certain types of treatment from you. The exact way you were taught to treat other people varies, but people deserve certain levels of love in the sense of “generic-benevolence” because they are an important person in your life, a fellow member of your community, or just someone who happens to be in need. Acts of self-denying giving in these contexts are all good and they are fitting. God created us to live in relationship with one another, giving for the good of the other. But these acts are not what 1 John has in mind.

1 John focuses in on God’s special act of love, his choice of a people to give himself to in self-denying compassionate devotion so that they may benefit. Anyone can experience this love—you must be born of God. Having received this love and benefited from it, it becomes the pattern and model for the love we give towards each other. And, significantly, the family identity as children of God and the power of the Spirit within us empowers us to give this (sort of) love to each other.

Acting towards one another in ways that reject giving this sort of love, that is hate. It is hate because it is willfully choosing to reject God’s pattern of love for the family which he has already extended to us.

Love in 1 John is like a little piece of God planted into you. This seed of God is meant to grow and give a continual harvest of blessings towards other followers of Jesus and to the world.

While 1 John focuses mostly on loving other believers, the pattern of love we see in Jesus is a pattern extended towards everyone, whether they know and receive it and benefit from it or not (1 John 2.2).

Where to start? One of the wisest things to do is pray: Spirit of God, give me opportunities to be loving to others; show me how the love of God which is planted in me ought to be lived out day by day.

If you have ever seen the movie Pirates of the Caribbean (preferably the first one, which was a good movie, as opposed to the rest, regarding whose quality I raise profound doubts), you may remember that captain Jack Sparrow has a compass that is unique. It doesn’t point north. Instead, it points the way towards whatever your heart most deeply desires.

The Spirit of God in our lives is kind of like that. God’s Spirit continues to point the way towards the heart of God—and God is love. We need to get better at reading the compass points because they will always guide us to acts of love for others.