God’s judgement and hell: restorative and retributive justice

Is God just? This question is bound to come up when considering what the Bible says about human destiny. After all, the Bible claims that those outside of Jesus will be punished in hell with no chance of change. While the exact scope and form of that punishment is not clear, there is no doubt that it is fearful, awful, and horrifying. How can God be just if he condemns people to hell? That’s a multi-layered question and here I will take a stab at one part of it: the difference between restorative and retributive justice.

At the outset, note that defining “justice” is notoriously difficult. I like to say that justice is “that state of affairs when perfect love of God and love of neighbor will no longer move our hearts to anger or sadness.” While a pretty idea, it is rather vague in practice. Further, most of the discussion about justice in our culture doesn’t give a hoot about theology. As we think about justice, here is a good touch point for how the concept of justice is commonly understood:

The most plausible candidate for a core definition [of justice] comes from the Institutes of Justinian, a codification of Roman Law from the sixth century AD, where justice is defined as ‘the constant and perpetual will to render to each his due’.

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Justice as a moving target

To start making sense of how God can be just if he condemns people to hell, we do well to acknowledge that there is no agreed upon idea of what justice is. We have many different options for what we mean by justice today. When we try to make sense of God’s justice, we need to be careful. We can easily decide what justice ought to be and then blame God because he does not act like we tell him he should. It may be the case that our idea of justice is out of sync with God’s justice. Maybe our trouble with hell is due, in no small part, to God’s justice not making sense to us anymore.

We could call this relativity. A quick glance across societies from the past and present shows a wide variety of ideas regarding justice and judgment: do we chop a thief’s hand off, put them in jail, or make them pay restitution? Some people believe that justice demands each one of these judgments (and that the others are unjust). In practice, people tend to operate as though our idea of justice and judgment is both universal and obvious. In the US, we send criminals to jail because it is the just thing to do. Doesn’t everyone agree?

Recognizing that our idea of justice is neither universal nor self-evident is a good start. Knowing that there are different ideas of justice should caution us from absolutizing our current notions and demanding that God conform to them. To make sense of hell demands that we are willing to check some of our own assumptions about what must be right at the door.

God’s justice

To make sense of God’s justice, we need a proper frame of reference. A framework that does not simply assume the way we do things in the US in the 2020s (over which there is much debate in the US) is just. If we are to have any hope of making sense of the biblical teaching on hell, we have to realize that God and hell do not function according to the dictates of the US penal code. God’s justice is not dependent on the standards of behavior, payment, and consequences which our society decides are just at this point in time. God’s justice fits within the special relationship he has with all people as Creator and Covenant-Maker.

The biblical conception of God depicts him as one who is just or righteous, and who as such remains faithful to the demands of a relationship with human beings that is divinely established and constitutive of human well-being. God’s justice may be expressed in deeds that liberate the weak and vulnerable from bondage, as well as in judgment on the unfaithfulness of the people; yet both expressions reflect God’s role as Lord of a covenant relationship. Correspondingly, the justice of human activity is measured by its faithfulness to the covenanting God, who may be identified in creation and history, in the Law and the Prophets, and ultimately for Christians, in the story of Jesus Christ.

William Wepehowski, Dictionary of Christian Ethics, 330

In short, justice is whatever God does to set all things right (for more on the idea of justification and righteousness, see justification by faith and the courtroom). Justice is whatever puts things back into the pattern of how God created the world. And human activities are just insofar as they reflect the way God has ordered the world. Judgment and hell fit within God’s justice as the proper response to those who refuse to submit to God’s ways, who refuse to live in the divinely established ways of the world which ultimately lead to human well-being.

Justices observed: restorative and retributive

At this point, I find it beneficial to build upon two different notions of justice and judgment to help us see how judgment—including the judgment of hell—fits within God’s commitment to the world he created and to human well-being within that world. These ideas are restorative and retributive justice.

Restorative justice

In contemporary society, the idea of “restorative justice” is gaining more and more sway. Restorative Justice

is a response to wrongdoing that prioritizes repairing harm and recognizes that maintaining positive relationships with others is a core human need. It seeks to address the root causes of crime, even to the point of transforming unjust systems and structures.

“Three Core Elements of Restorative Justice“

Restorative justice finds justice in fixing and maintaining rather than punishing. The idea is to bring about a state of justice through releasing the tension, anger, fear, etc. which stands behind the act of violence in the first place. At issue here is the question, “What good can come out of the wrongdoing that happened?”

Restorative justice has been making inroads in areas like how discipline should be handled in schools all the way up to criminal cases.

Retributive justice

Retributive justice is more what we are familiar with in the context of the US legal system. The phrase, “I paid my debt to society” summarizes the basic idea of retributive justice: those who commit certain kinds of wrong acts morally deserve to suffer a proportionate punishment. The punishment is good and right regardless of whether any good comes to the person who was wronged. The death penalty is the ultimate form of retributive justice. The death penalty exacts justice by rendering a punishment deemed proportionate to the crime upon the guilty one, even though there is little to no demonstrable good which comes either to those who were wronged or to society at large. Retributive justice says that the just demands of good and right be upheld because they are good and right even if no one derives immediate benefit.

Of course, there are many ways which society can benefit from the quick and effective execution of retributive justice. They may not be immediately obvious, though, and the benefits may not accrue to those immediately affected by the crime/injustice at hand. The idea of benefits coming from justice is a useful low-level way to distinguish restorative and retributive justice, but it is not the whole story.

Summary

Much more could be said on either of these, as well as alternate theories of justice. Note, though, that justice is not the same as punishment. Sometimes justice moves in to restore a relationship; sometimes to restore stolen property; and sometimes to punish more directly. We embrace a mixture of different views of justice and believe that different ones should be used at different times. These different ideas of justice provide a helpful way to see what God’s justice is up to.

God’s program of justice: a both/and

The Bible, I submit, exhibits both these types of justice in action. God remains faithful to the demands of a relationship with human beings on the terms he has established as Creator and for the good of people. Both those must remain true.

God the Restorer: restorative justice

God is interested in bridging the brokenness between him and the world. Even though God is the aggrieved party—after all, humanity rejected and rejects God, not the other way around—he moves heaven and earth to make connection possible again. The good outcome he is looking for is relational connection to people whom he has created.

The entire gospel program is the ultimate program of restorative justice: God aims to bring his kingdom into the world through Jesus. In reaching out to humanity through Jesus, God seeks to short-circuit the system of sin, effect rehabilitation, address the suffering of victims and perpetrators alike, and create an environment where the marginalized are cared for. God exemplifies restorative justice. This is the easier part of God’s justice to deal with.

God the Avenger: retributive justice

However, God’s judgment is not exhausted by restorative justice. It contains a significant measure of retributive justice as well. God will exercise retributive justice most clearly at the end of all things. He will move into the world as an Avenger, bringing punishment where it is due.

What is God avenging in the punishment of hell? I submit that he is avenging his world. And, more profoundly, he is avenging himself by setting all things back to the way he created and intends them to be. For as long as God is reaching out to world in the move of restorative justice, he is choosing to bear with creatures who reject him and his intentions for them and the world he made. Restorative justice aims to redress those harms while there is still time. The attempts at restorative justice, though, have a limit.

The limits of restorative justice

There are at least two reasons why restorative justice is always limited: (1) temporal and (2) the integrity of the person.

Temporal limit of restorative justice

Temporally speaking, once one party in the victim/victimizer set is gone (whether dead or no longer present), any hope for restorative justice is gone. If a thief empties your bank accounts, spends all the money, then dies, restorative justice is simply not on the table. While the factors are a little different in that God is eternal and human beings will have an eternal existence, there is a temporal limitation. As the Bible lays it out, the time to engage with God in restorative justice is now. Not later. Death is the threshold past which all opportunity to turn towards God and engage his restorative justice in Jesus ceases.

There are some who argue for a postmortem evangelization, as if Jesus shares the gospel with everyone after they have died. While I sure hope that is the case, it is pure speculation. Nowhere in Scripture is such a thing revealed.

And so, if God is going to exact justice (set all things back in order)—and he has made it quite clear that he will—restorative justice ceases to be an option when the sinner dies.

Integrity limit of restorative justice

The second limit on the effectiveness of restorative justice is the concern for (2) the integrity of the person. Eventually, attempts at restorative justice will either work and effect change in the relationship between victim and victimizer, or they will not. There is no guarantee that people will change if just given more time. Like the habitual liar whose identity is so deeply wrapped up in their lies that they can no longer admit the truth and also remain true to who they believe they are, people who identify themselves as foes of God seem to lose the ability to enter into restorative justice with God.

In the case of sinful humanity, the basic grievance all human beings have against God is that he exists and that he has rights over us as God and Creator. Unless we are willing to drop our grievance against God, there is no way that he could enter into restorative justice with us. Unless he were to fundamentally destroy some part of us.

It seems possible that God could unmake and remake everyone by force. Then they would acknowledge him as God. But that would involve marring his creation at a fundamental level. God is committed to the integrity of his creation. Destroying our human ability to turn to God in love—which requires also the ability to turn away from God in spite—would be to destroy the very human well-being which God is committed to protecting in his justice.

And so, we reach the crucial point of the matter: God is committed to his creation the way he created it to be. God reaches out to wayward humanity through his restorative justice, but if anyone refuses that, then God must either: (a) give up his claim and rights as God to establish the world as he sees fit, or (b) bring justice through a fitting judgment against the rebel to his will.

Retributive justice ultimately acknowledges the integrity of the being who says to God, “Justice cannot be served so long as thou art.” Retributive justice—condemning to hell, in whatever exact fullness of details that means—is God yielding up such people to their own settled choice. In rejecting restoration, they choose retribution.

Hell and God’s justice

As we try to make sense of hell and its role in judgment and justice, there are many difficult questions to balance. It is important to remember that the point of judgment is not to let God blow off a little steam when he gets frustrated with how things are going on earth. The point of judgment is to channel humanity back towards God and the well-being for which he created us.

Judgment is meant to be restorative, bringing about restorative justice. It aims to bring people into relationship with God. Yet, many people refuse to submit to God on his terms and find the human well-being we were created for. Key to the reality of hell, though, is that our refusal does not change God’s commitment to the integrity of his creation. Whatever exactly hell entails, it is the removal of rebels to God’s will from within his creation. God’s retributive justice flows from his commitment to justice (setting the world in order as he created it) and his commitment to the integrity of human beings as he created us.

if we refuse God as God, then justice. And the final act of justice can’t be anything other than retributive.

February 19, 2023 Church Service

On death and dying today

God created us to live in bodies. And bodies die. Everyone dies eventually. Barring the imminent return of Jesus, anyone reading this will die sometime in the next few decades. A cheery thought to make your day. While I don’t suppose dying has ever been simple or fun, it has taken on a certain measure of difficulty and complexity in the times we live in. Dying can be really difficult, in many different ways. Being far from an expert on the matter, I wanted to share a couple thoughts on death and dying today.

The most immediate impetus for this came while reading a recent article by R. R. Reno in First Things. He writes:

Over the last few years, Canada has rolled out a program of doctor-assisted suicide. Originally restricted to those facing “reasonably foreseeable” natural death, in 2021 it was expanded to those whose illnesses need not be terminal. the Canadian government is considering an expransion of this program to cover “mature minors,” including those as young as twelve, who are deemed “fit” to make a decision to end their lives. These policies are widely popular. Polling suggests that 86 percent of Canadians approve of a “right” to die. We should not be surprised. As Leila Mechoui explains in Compact magazine (“Euthanasia Is LIberalism’s Endgame), “State-administered euthanasia on-demand is the logical endpoint of a society built on secular himanism and utilitarianism. These frameworks preclude any appeal to an absolute authority beyond the individual. The ultimate expression is as a state-protected ‘right’ to a ‘dignified’ death.” The future of the West: a culture of death under the sign of choice.

R. R. Reno, “The Public Square“

A culture of death. A culture where we come to feel that we are not truly alive and not fully human unless we have the right to kill others (abortion) and ourselves (euthanasia) when life is not desired any longer.

There’s a lot that could be said about this. I want to share three resources here that may be helpful in thinking about a culture of following Jesus in the midst of a culture of death.

Look here

Joel Cho, a doctor in San Francisco reflects on the role of a long obedience to Jesus when it comes to death and dying in A Doctor Shares the Secret to Dying Well. I especially appreciate how he talks about many people being “bewildered by death.”

Mélodie Kauffmann, a nurse in France, reflects on the human difficulties of suffering, especially as a caregiver for someone else who is dying, in Job’s Wife Urged Him to ‘Curse God and Die.’ Caregivers Get It. The suffering is real for all involved. We would do well to remember that, for most people, the “culture of death” is driven not by reasoned ideology, but by fear and compassion. Fear of suffering and death; compassion on those suffering expressed in a desire to end the suffering as soon as possible.

Last, check out this paper I wrote on passive euthanasia, active euthanasia, and suicide. It began its life in a seminary ethics class. I have thoroughly revised it and offer it as food for thought.

A farewell to death

The hope in Jesus is that one day we will get to say “farewell” to death forever. We look forward to what Paul writes:

Death is swallowed up in victory. O death, where is your victory? O death, where is your sting? The sting of death is sin, and the power of sin is the law. But thanks be to God, who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ

1 Corinthians 15.54b-57 (ESV)

Until that time, we will live and labor in a world where death is a tyrant and terror. The great hope is that Jesus has blazed a trail through death and can lead us through it into life. But even knowing that doesn’t make it easy to live faithfully in the world of complicated death and dying.

February 12, 2023 Church Service

February 2023 Informer

Justification by faith and the courtroom

In the New Testament, especially in the writings of Paul, a group of words show up frequently that we translate as, justify, justification, and righteousness, depending on the context. This concept comes from the legal world. A key idea in the concept is “to be in the (legal) right.” Recognizing the legal background is helpful. It is also helpful to know that the legal background works a little different than what we assume. This different legal background helps to underscore that justification has to do with God setting things right in the world.

Creation and Covenant in justification

Categories of creation and covenant stand behind justification. The juridical reality of justification is not about God deciding what is right between two different parties, as though that is up for debate. Rather, God has determined a right order for the world, as expressed in creation and covenant. As Creator, he intervenes to reestablish this order, particularly in defense of the marginalized.

Justification and the courts: a legal analogy

Since justification is a legal concept, we do well to consider how the idea in the Bible relates to the legal world.

The modern courtroom

In the modern courtroom, there are three parties: the plaintiff (those suing/accusing), the defendants (those accused), and then the judge. There may be lawyers, witnesses, juries, etc., but these all nuance the three party system, rather than adding a new party. A lawyer serves the interests of the plaintiff or defendant, a jury assists the judge, etc. In this system which we are used to, the judge is a neutral outside party who has the authority to settle the dispute. In a modern courtroom, justice is administered by a non-partisan third party.

The biblical courtroom

The vision of court cases arising in the Old Testament literature is different. Especially in the poetic and prophetic literature, God is pictured not as a neutral third party judge, but as someone involved in the contention.

Let me quote a chunk from New Testament scholar Mark Seifrid:

“It is important to recognize that the modern three-party courtroom is not an appropriate model for interpreting the biblical conception of justification, including that of Paul. The administration of justice always is a two-party affair. A more powerful third party who entered into a dispute took up the cause of one disputant or the other. Therefore, when God enters into a contention, he is not pictured as a judge who stands above the matter, but as a party to the dispute. In effecting justice for the one in the right (‘justifying’ them) and punishing the one in the wrong, he establishes his own cause, as in Psalm 98. His verdict, moreover, does not merely bring salvation, but re-establishes moral order within the world and his authority as creator over it. It is not that might makes right – as one must say, if one reduces ‘righteousness’ to the idea of salvation – but that God’s might restores what is right, especially his right as God. For this reason, we find the occasional confessions by the defeated parties that, ‘Yahweh is righteous, we are in the wrong’ (Ex. 9:27).”

Mark A. Seifrid, “The ‘New Perspective on Paul’ and Its Problems,” Themelios 25, no. 2, 15.

Let’s unpack that a little.

God as disputant enforcing the standard

The key point is that God is not a neutral judge. God has a vested interest in the cause of one party against another. God enters the courtroom as the “muscle” to accomplish what is right. And “right” is what is in line with God’s character and covenant promises.

Key in this whole arrangement is that God moves to enforce the standard. That is, he steps in to establish righteousness. We might summarize righteousness as “conformity to the way things are supposed to be.” Within the worldview of the Bible, that means “in line with how God created them to be.” Thus, living in love toward God and others, living in conformity to God’s will, etc. At the center of righteousness is God. He, as the Creator, establishes what righteousness is.

God enters into the dispute with his power to act on behalf of the one being wronged. And he shows up as a force for righteousness, a force to restore his world to order and deal with anything that stands in the way.

God the Adversary or Lover

Taking this background into the New Testament, we can more readily see that the problem humanity has is not to somehow convince God to judge in our favor, but to somehow avoid being destroyed by God. When God moves in to establish righteousness in his world, we will be destroyed. Unless we can someone be put to right before God moves as a righteous adversary against us.

The Law, the promises, God’s work in the world, these are how God has moved in history to provide a way for people to be righteous. That is, for sinful humanity to fit in once again with the pattern of the world that God made. That way, when he approaches us, it will be an embrace of love rather than destructive judgment.

When we talk about judgment, it is not as though God has a personal vendetta against you, me, or anyone else. He is not sitting in heaven with a divine axe to grind, just waiting to smite you. Instead, the picture in Scripture is of a God entering into humanity. But his approach will either destroy or give life. And the difference is whether we can find a little piece of righteousness to hide ourselves in. That way, God can be just to himself and also just to us, because we would be righteous, we would belong to the pattern.

Justification by faith is how God provides a little piece of righteousness for us hide in. Actually, it is an enormous piece of righteousness. It is Jesus, the Righteous One.

The grand story of the Bible is the story of God reaching out to humanity in a way to bring restoration, rather than destruction.

Photo by Tingey Injury Law Firm on Unsplash

February 5, 2023 Church Service

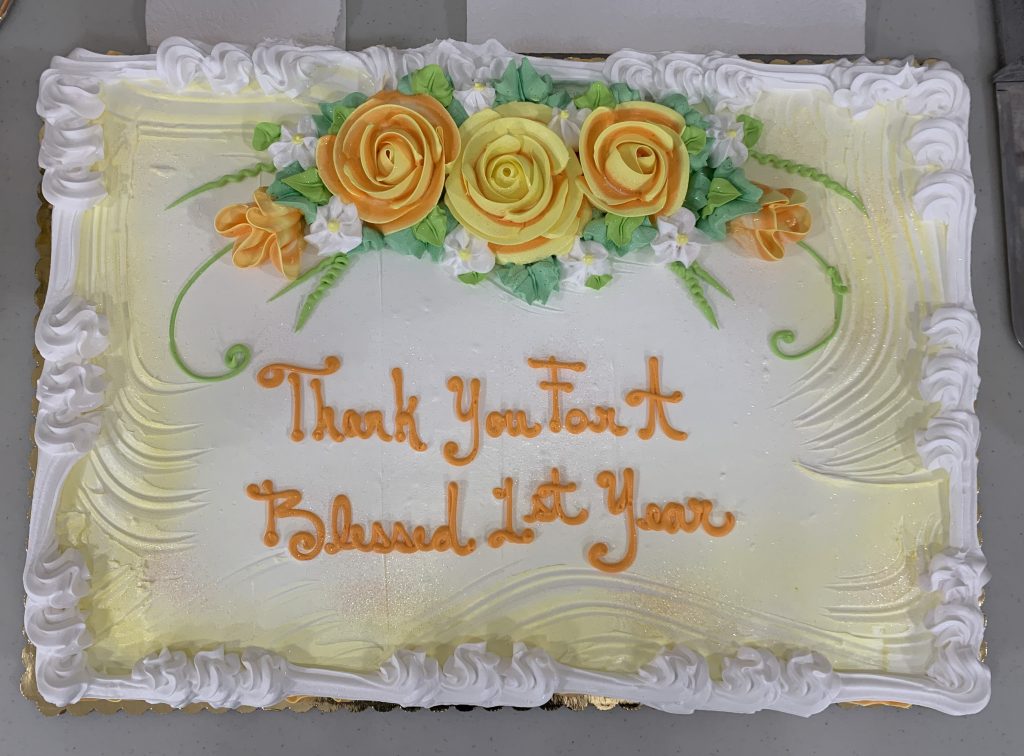

Celebrating One Year of Service

On January 15, 2023 we celebrated Pastor Nat Erickson’s one-year anniversary with First Baptist Church. The Erickson family moved into the church parsonage on January 20, 2022, and Pastor Nat preached his first service on Sunday, January 23. The church has been blessed by his leadership and guidance, and whole Erickson family’s presence and involvement in the life of the church. Thank you, Ericksons, for the blessings you have brought to us!

Erickson Family

Flower Bouquet

Cake