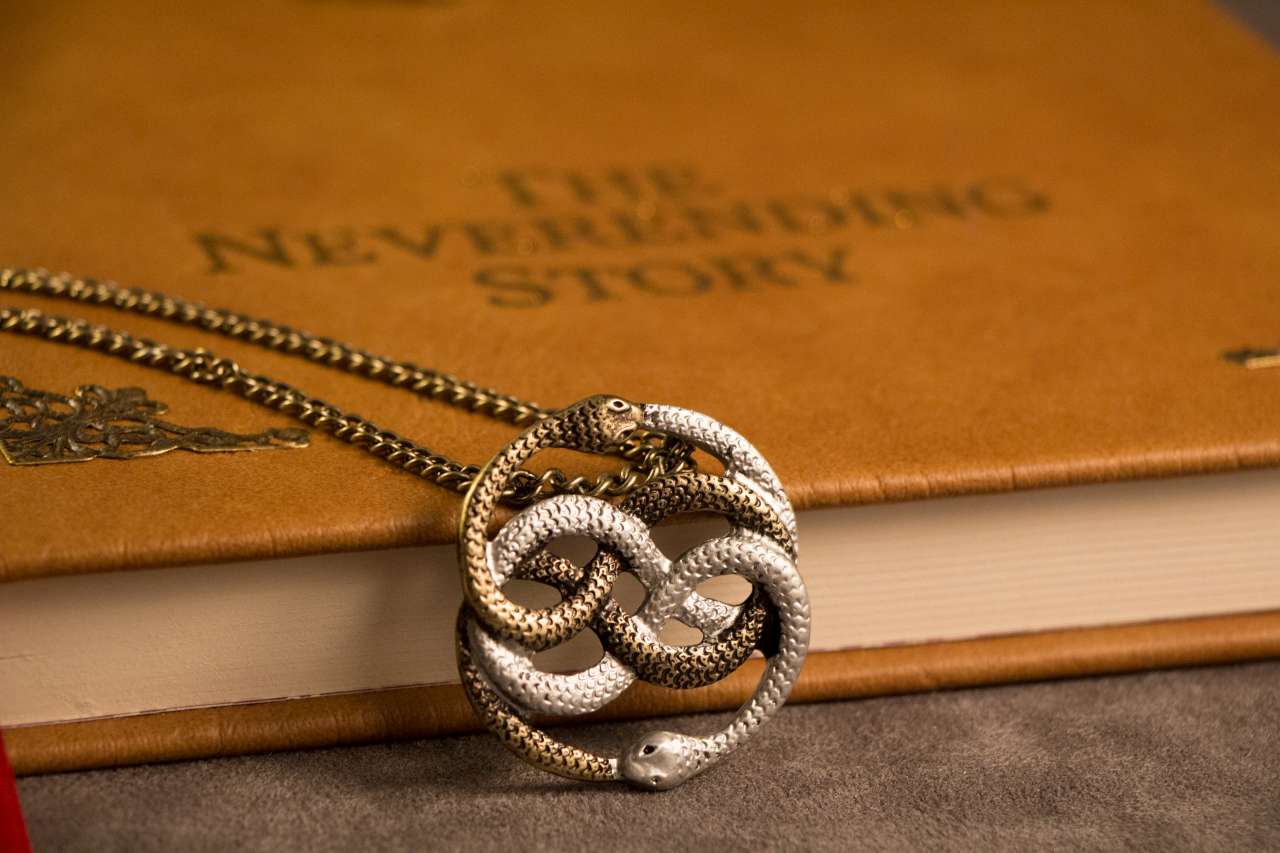

In the last post, I noted how I’ve been falling into the rabbit hole of online news. To switch metaphors, it is like a bug-zapper. Something about it keeps drawing me in, even though I know that getting too close can be perilous. The endless stream of novel stories just waiting to be read beckons me on. How shall we be sensible and faithful in engaging with the world of digital news (or TV news, for that matter)?

Fitting the rabbit hole into life

Orienting principle: there is nothing wrong with reading the news. There can be great benefit in it. But if you find yourself in a place like me where turning to the news becomes a burden, a time-sucking draw, it may be time to climb a little out of the rabbit hole. Here are a couple things to consider for engaging with the news in a faithful way.

The limits of your time

It should go without saying, but needs to be said anyways, that our time is limited. Whether that be my time at work while preparing sermons and prepping other things for church, or our time with our families, or your time doing whatever it is you like to do. We all have limits.

An ever-present threat from online news, or TV news (or any sort of online activity) is that there is no end. There is no natural disengagement point. Movies end. Games end. But you never reach an end with online news, so you never need to stop.

Since the news never runs out, we must be careful of what amounts of time we allow ourselves to spend in engaging with it. Ask yourself how much time you can beneficially spend perusing news stories, then set some way to enforce that time limit.

I'm trying out a browser extension (LeechBlock) on my computer at work to limit the amount of time on different news sites the 10 minutes per every two hours. That's enough time to browse through, find some worthwhile stories, and get back to work. The goal is to make engaging with the news a part of a broader strategy of preparing for ministry each week, rather than a way to escape from preparing.

It’s worthwhile for all of us to consider the limits of our time and how we engage with the news and other digital media.

Consider the limits of your circle of care

The global scope of online news makes it easy to forget that we have limited circles of care. What is a circle of care? There are only so many people, so many groups, and so many institutions which we can be involved in and meaningfully care about. There are only so many topics about which we can even be marginally informed, and a very tiny amount that we can be an expert on. It should be humbling to consider the vast number of topics about which each of us knows absolutely nothing.

The news provides a smorgasbord of information that far exceeds any individual’s circle of care.

It’s easy to think that my circle of care is far bigger than it really is. But at some point, you have to wonder how much should I really care about the pink dolphins in the Amazon river and how the global environmental situation affects them? While my heart goes out to people protesting in Iran over the recent death of Mahsa Amini, how much do I really care? Better yet, how much time and effort should I spend in caring about it? How relevant is it to my life and the lives of people I live with?

There are no easy answers to this question, but it is a question that we need to ask ourselves periodically.

A practical way to deal with the limits of your circle of care is to come up with a few areas of the news you want to be informed on. Then go find websites which address those areas. Avoid news aggregating sites; they will always bring you things outside of your circle of care. You’ll never hit the bottom of the rabbit hole you’re falling down.

Some news sources I frequent: WIRED, Christianity Today, and Spiegel (a major German news outlet)

The limits of your mental/emotional care

Related, it is important to consider the limits of our mental and/or emotional care. We all have a finite amount of love, concern, and care that we can give. There are more things in the world to care about (and that are worthy of caring about) than we can possibly care about in any meaningful way. Where we use up our care impacts every part of life.

If I have 10 units of emotional care that I can give in a day, and I spend five of them reading different news stories that have very little direct impact on my life, what effect might that have on the people who I go home to live with after work? I have to wonder, how much of my emotional and mental capacity am I spending trying to find and understand crises here there and everywhere around the world, and what sort of state is this leaving me in for when I go home and one of my children is having actual crisis that requires my mental and emotional attention?

Too much attention to the news can burn up our capacity to care for the people in our lives.

You are only human

In summing up these considerations, the main point is that I need to take a little time and remember that I am only human. And I mean that in the best possible sense that one can mean it. Being only human is not a bad thing; It is a glorious thing. But if we try to live as demigods, while only having the capacities of a human, we end up short-serving everyone we really live with.

One of the fascinating and wonderful things about being only human is that our abilities are well-suited for caring for and helping people who are connected to where we actually live in life. There are good and appropriate ways we can learn about and be concerned about things happening on the other side of the world. But the chief measure of loving your neighbor is not how much care you have for people on the other side of the world, but how much care you have for people on the other side of the street.

Pulling out of the rabbit hole

Over the course of this week, I’ve been doing some thinking and planning to engage with the online news in a more limited and focused way. I doubt I have the answer, but I want to engage in a searching for better practices in how to use online news in life and ministry. The rabbit hole is there, it is bottomless, and it has an endless draw for those who look to peek their head into it. I’m working on doing better at standing on my own two feet and not falling in.